Unexpected curves: Drawing straight lines on a map

An introduction to geodesic lines. Not very intuitive, but much more useful than drawing simple straight lines on a map.

Something that catches the attention of those who have not spent time thinking about maps is the representation of the shortest distance between two points. Although almost everyone knows that maps distort reality, when someone asks us to draw the shortest line between two points on a map, the first impulse is to draw a straight line between the two (more or less replicating what we experience in the physical world). The approximation can work in some cases, which will depend on the projection used, or when the two points are close together on the map1, but often the solution will be much more complex than expected.

This is much easier to accept when you see it for yourself. If you have a globe at home and a piece of string, just draw lines and observe that in some cases the paths are not as intuitive as they might seem. These lines are known in geometry as geodesic curves. Today I bring you some examples and, from there, I will derive other curious lines that can be drawn on the planet.

Airline routes

If you have ever taken a transoceanic flight without changing hemispheres, or between Europe and Asia, you will probably have noticed that the trajectory followed by aeroplanes is not usually a straight line on the map. The first time I experienced it was when I crossed the pond for the first time. I had just changed jobs and, surprisingly, I was being sent to a training course in Boston for a few weeks. Due to scheduling, I had to make a stopover in Munich, so the trip turned out more or less like the one you can see on the map below.

I had read and studied cartographic projections, but the truth is that when I saw this for the first time, what came to mind was that there were other reasons why the chosen route was that one. I assumed that, having to spend so many hours over the ocean, it was a matter of safety to leave Europe via the British Isles and enter North America via Newfoundland. In my head, it sounded good enough and, in a way, the perfect explanation. It's fascinating how we can fool ourselves when we are really convinced of something.

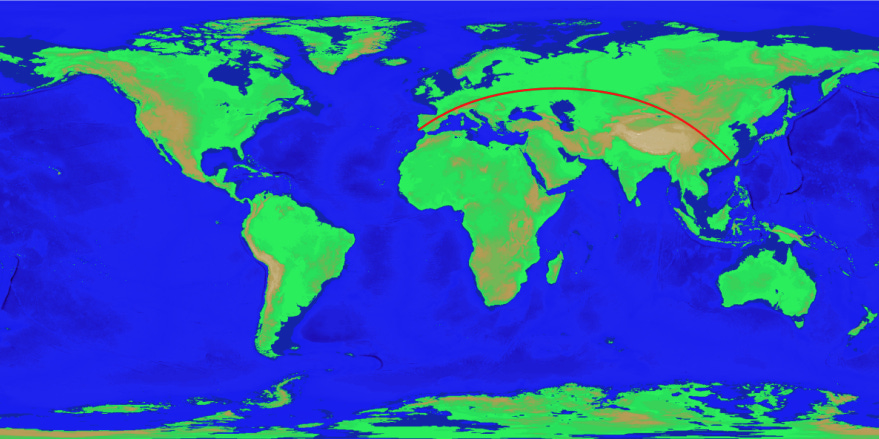

A few years later, I had another long trip, but this time in the completely opposite direction. I went to Japan to visit a friend and, for reasons of cost, I ended up flying from Madrid to London, and from there to Tokyo. The route was similar to what can be seen on the following map2.

Here my mental scheme collapsed. In this case, the cheap explanation I came up with for the trip to Boston no longer worked. It's not that we're talking about a slight detour, it's that in this case the plane was flying over the Arctic Ocean for a while, tracing a curve on the map that is not at all intuitive.

I took a slower look at it and, as soon as I read it, it became crystal clear. Planes, in general, use the shortest routes between two points, for a simple matter of fuel costs, as it is logical, but these routes correspond to the geodesic lines on the Earth's surface, not the straight lines on the map. Taking the map above, the distance separating London and Tokyo following its geodesic line is 9,576 kilometres. If, on the other hand, we draw a straight line on the map and measure the distance, we get more than 11,200 kilometres, an increase of 17%. That's something.

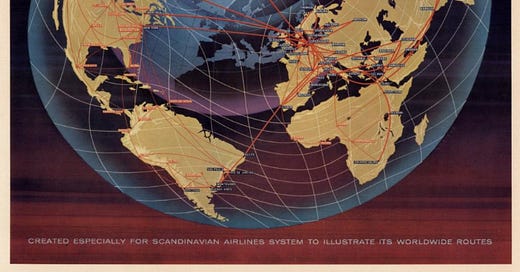

During the first decades of commercial aviation, airlines advertised with a multitude of maps so that potential customers could appreciate the great distances that could be travelled thanks to the new technological advance. As is to be expected, those first maps had the limitations of the technology of the time: aeroplanes could fly a minimum distance before stopping to refuel, which meant multiple stopovers and, consequently, taking advantage of the opportunity to travel through populated and interesting areas. This is why some airlines draw practically straight lines on the map along their entire route, as in this example from the Dutch airline KLM.

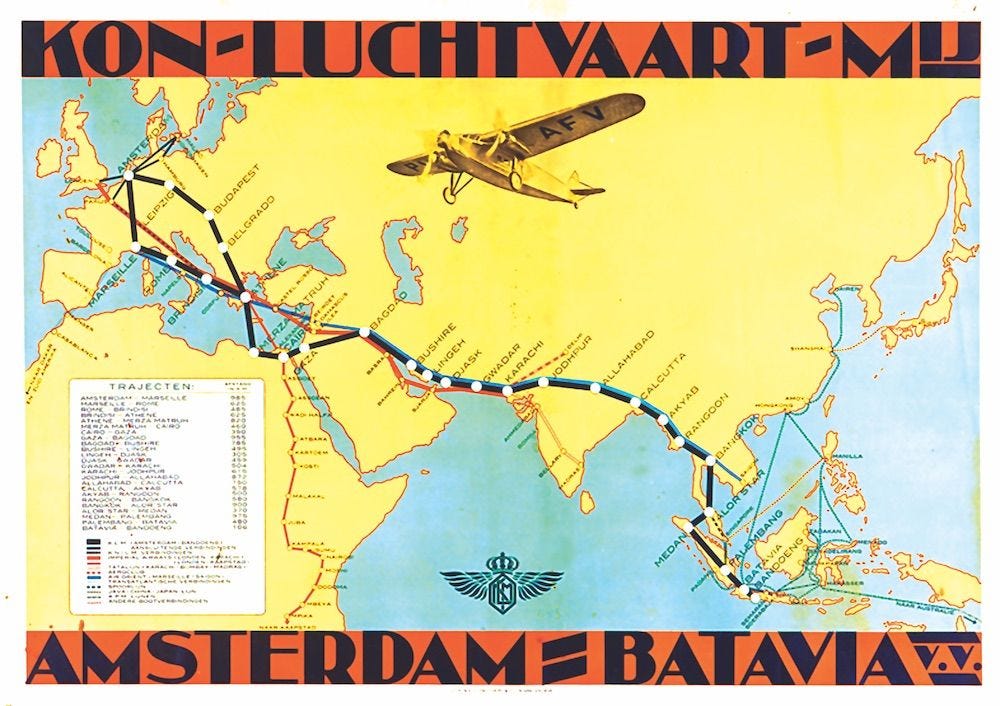

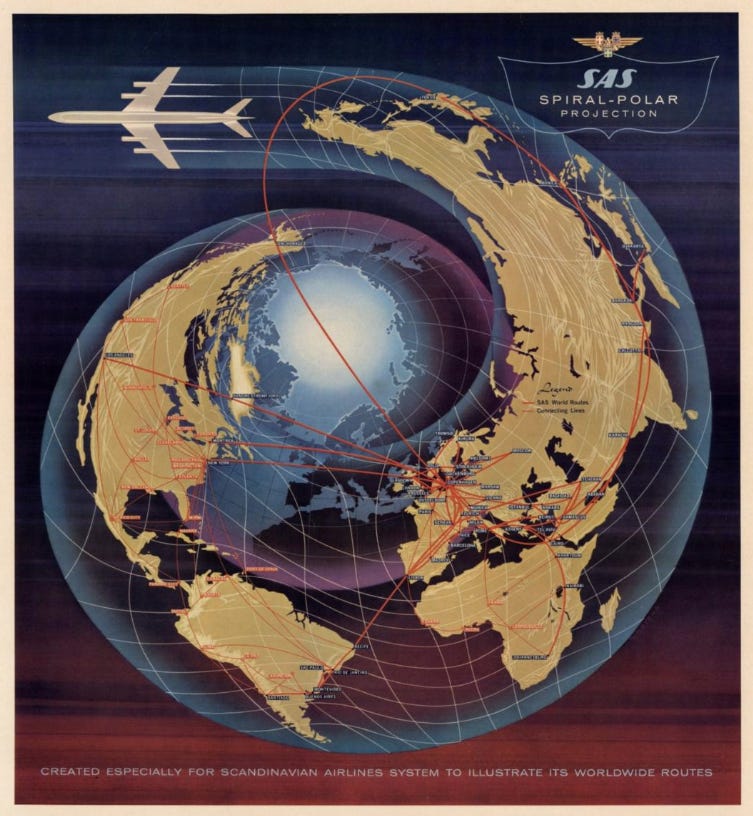

With the passing of the decades and improvements in the range and safety of aeroplanes, journeys began to become more efficient, which was also reflected in the flight route maps published by the airlines. Perhaps the most iconic maps are those published by SAS (Scandinavian Airlines Systems) during the 1960s and 1970s. Using unusual projections, they effectively showed how aeroplanes could make journeys impossible for other means of transport.

The map below clearly shows a flight between Copenhagen and Alaska that directly crosses the Arctic Ocean.

Facing Mecca

According to the Muslim religion, all the day's prayers must be made facing the city of Mecca, where the Kaaba is located. This is also decisive in the orientation of mosques, as these buildings are constructed in such a way that prayer within them is also oriented towards Mecca.

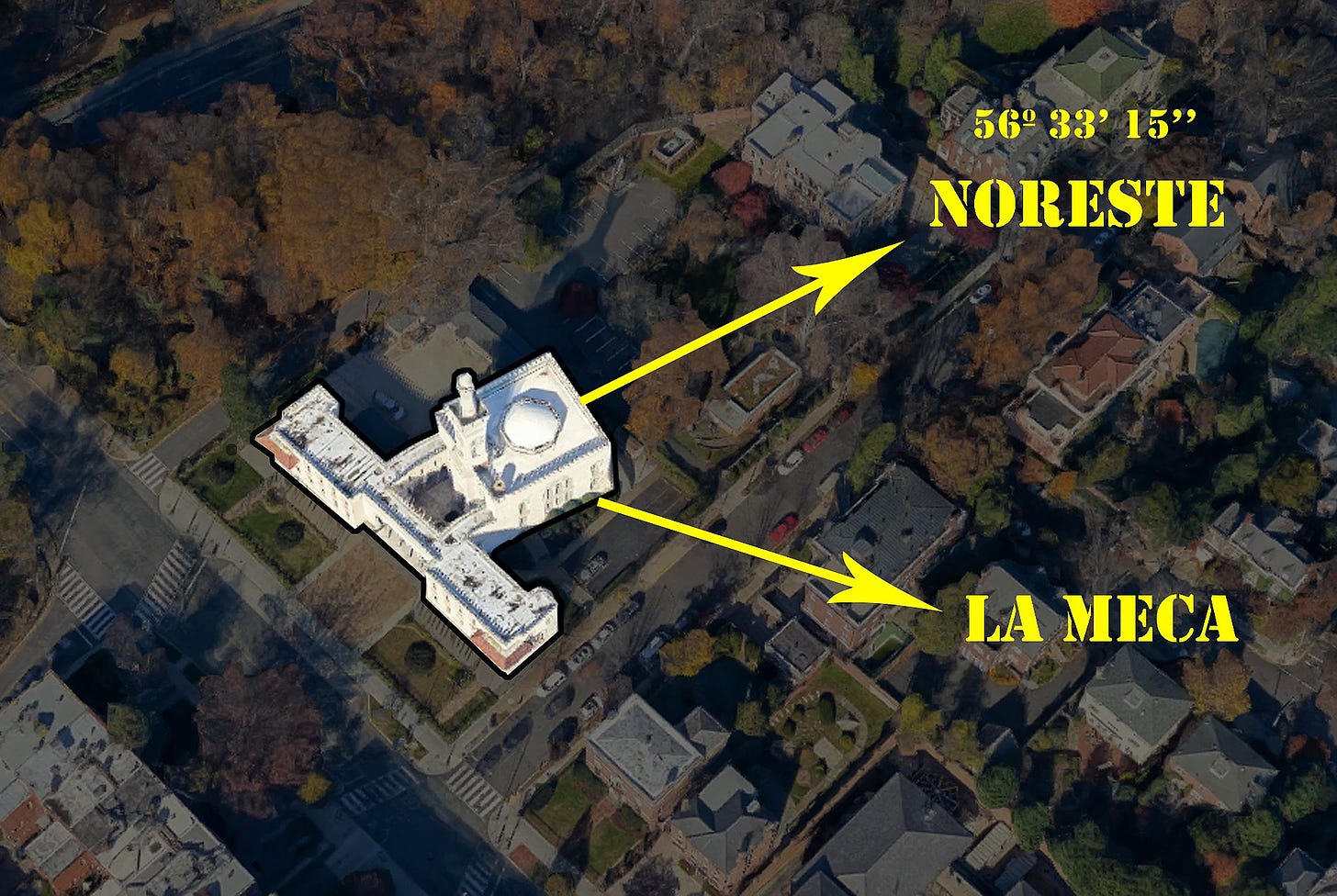

The Islamic Centre of Washington was built between 1949 and 1953 and, following Muslim tradition, it was built with the prayer facing Mecca. Shortly before its opening, the building was visited by Kamil Abdul Rahim, ambassador of the Arab League to the United Nations, and he questioned whether the orientation of the building was correct. Mecca is located east-southeast of Washington, but the building pointed northwest.

And here we find ourselves once again with the same dilemma we have been discussing with the airlines. The geodesic line that joins Washington and Mecca corresponds to the orientation of the mosque, which you can see in black on the map below. On the other hand, the straight line that can be drawn on the map corresponds to the direction that Kamil Abdul Rahim interpreted as correct, in orange on the map below. Somehow, depending on the interpretation, it appears that both options are correct.

Which one does Islam consider correct? When there was no access to any tool to establish where Mecca was located, each region usually had indicators at their local mosque. In general, west of Mecca it was advisable to pray towards sunrise, while east of Mecca it was towards sunset. With the popularisation of compasses, this idea was passed on as the most practical way for any Muslim to face Mecca.

The truth is that Arab mathematicians solved this dilemma several centuries ago. The best way, according to them, is to orientate yourself following the geodesic line, or what is the same, following the shortest distance that separates you from Mecca. As is to be expected, the Muslim religion is sufficiently lax as to admit any approximation as correct.

So, returning to the building in Washington, the architect was right, not so much the ambassador.

The longest sea routes

Probably you’ve heard that one of the great things about the Mercator projection is its effectiveness for navigation. By its mathematical definition, it is a conformal projection, which allows it to maintain angles. In practice, this means that any straight line drawn on a map with this projection can be easily followed by a sailor, as long as he keeps to a bearing3. This was commonly used during the 17th and 18th centuries, when a large part of the planet's oceans were explored. But a peculiarity of the course is that it does not help to travel the shortest distance, it is only the simplest and most intuitive way to get from A to B.

The big difference between a bearing and geodesic lines is quite curious to explore. With the popularisation of Google Earth and Google Maps, many people have spent time plotting navigation routes using geodesic lines, so that unexpected points can be joined. In a way, this is the equivalent of thinking: if I stand on the coast and look towards the horizon, where am I looking? Incredibly, there is a point on the coast of Norway, near Bergen, that points directly towards Antarctica, but across the Arctic Ocean!

![r/MapPorn - You can just barely sail north from Norway to Antarctica in a straight line without hitting land. Album with close-ups in comments. [1273x647] r/MapPorn - You can just barely sail north from Norway to Antarctica in a straight line without hitting land. Album with close-ups in comments. [1273x647]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6ac2fdef-3cfb-46a6-98d2-50a0e68767c0_1636x831.jpeg)

Along the same lines, Patrick Anderson stated in 2012 on Reddit that he had found the longest geodesic line that could be travelled over sea without setting foot on land. It went from the coast of Pakistan to the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia. If you want something more visually attractive, you can have a look at this video on YouTube where he traced the same line on Google Earth.

![r/MapPorn - The longest straight line: you can sail almost 20,000 miles in a straight line from Pakistan to the Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia. [720x360] r/MapPorn - The longest straight line: you can sail almost 20,000 miles in a straight line from Pakistan to the Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia. [720x360]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa32e5afc-1fec-408a-96f9-1ce345f6429d_720x360.png)

This approach proved extremely appealing to Rohan Chabukswar and Kushal Mukherjee, a physicist and an engineer from India. They decided to dedicate time to formalising this approach and finding out what the longest possible route in a straight line really is. After five years of brute force analysis, in which more than 230 million possibilities were analysed, they published in 2018 that Patrick Anderson was correct4.

Specifically, the sea route would leave from a beach near Sonmiani, in Pakistan. It would travel along the east coast of Africa, cross the Mozambique Channel, which separates Madagascar from mainland Africa, until it reached the Antarctic Ocean. From there, it would pass between Cape Horn and Antarctica, cross the entire Pacific Ocean and finally reach the cold beaches of Karaginsky Island, off the coast of Kamchatka, Russia.

With all the data in hand, the authors of this study also revealed what the equivalent route by land would be, going from Sagres, in the south of Portugal, to the coast of China, near the city of Jinjiang5.

It is not possible to generalise, as the distortion will vary depending on the orientation of the line and the projection. But if we take a horizontal line with the projection used by Google Maps, it takes more than 1,000 kilometres of distance until you appreciate the curve.

It was a while ago. Now, not being possible to fly over Russia, there are two options, one of them flies over Alaska, Canada, and Greenland.

Bearing, by its mathematical definition, is the angle between the line from a point to the north and the direction to be taken. In other, more practical words, staying on course is simply a matter of making sure that we sail with the compass always pointing in the same direction.

Here are the details of the study in the journal Science. If you want the full paper, you can download it in PDF here.

You may have seen another similar route that goes from the Pacific coast of Asia to the Atlantic coast of Africa. This other route crosses the Dead Sea, so it is not usually considered correct.