Time zones: time standardization

How we went from each city having a local time, to a national standardization and, finally, with the well-known international time zones.

This article is part of a trilogy on time. You can read all the parts here:

Last week I talked about how the division of the day into 24 hours was established. At the end of the article, it was clear how we arrived at that particular division, and how the sun, at its highest point, marked 12 noon. But, in every city, town, and even village, noon occurs at a very specific time of the day that is shared only by the places that are on the same meridian.

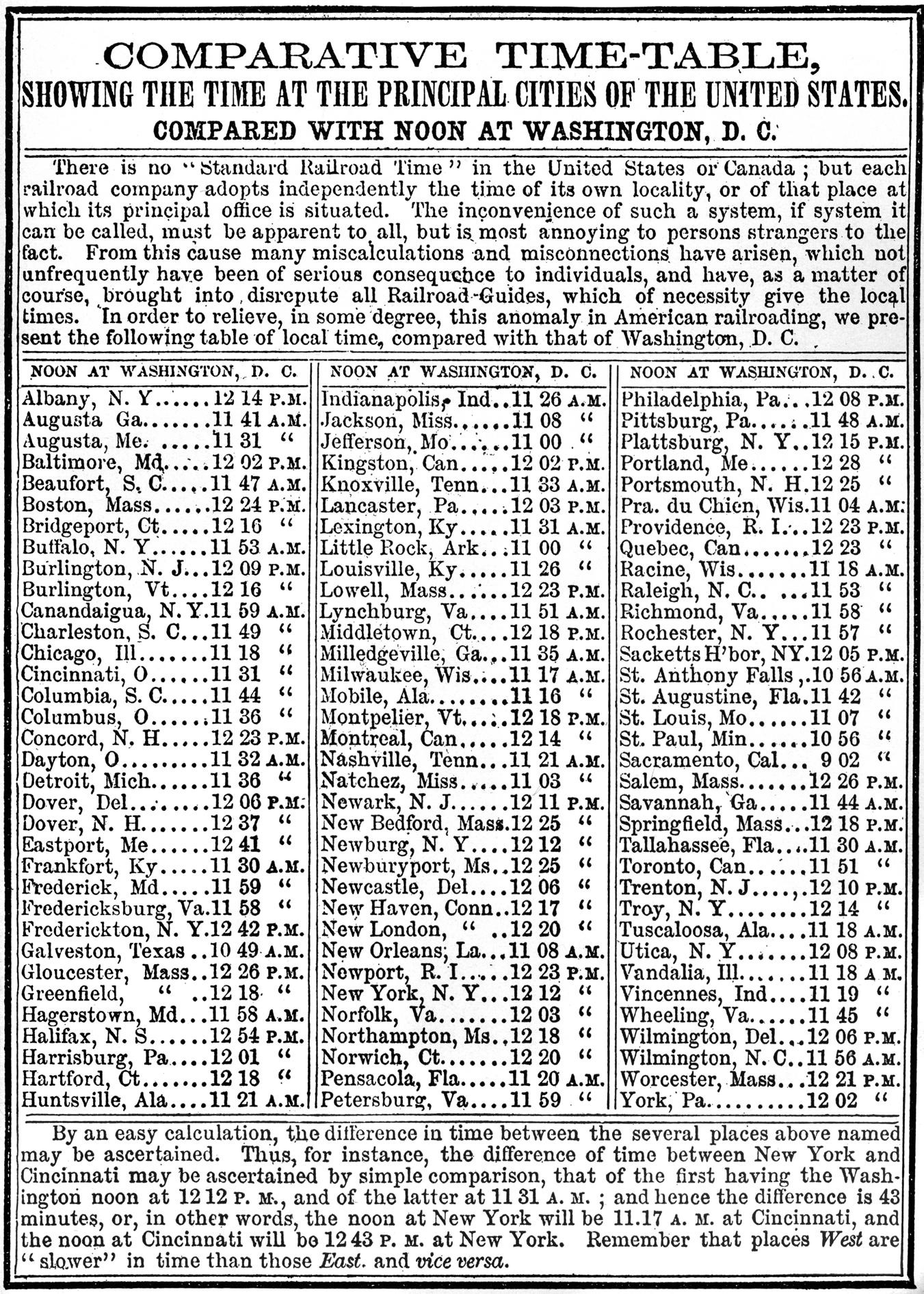

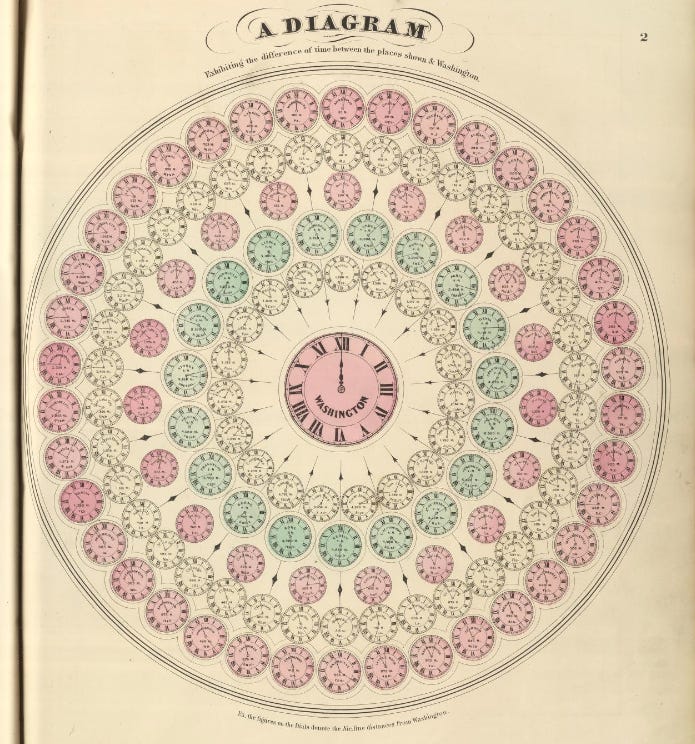

Am I saying that each town had its own local time? Yes, that's right. Here is a table published in 1857 showing the local time in 102 American cities compared to noon in Washington, D. C.

In 1857, when the clock in Washington was striking 12:00, the clocks in Baltimore, 35 miles (56.33 km) away, were striking 12:02. There was no synchrony between the two cities, but there really didn't need to be.

Today we're going to walk through the history of how we went from this insanity to worldwide standardization of time.

National standardization

Until the 19th century, each city operated completely independently. All events had a purely local character, regardless of what time it might be elsewhere. If the priest called the 10:00 a.m. mass, it was enough for the people who lived around that church to know about it. If there was a proclamation planned, following the time of the town hall was more than enough.

Travel between towns was something only the upper classes did regularly. These were the only people who had the luxury of carrying a pocket watch1, to keep track of the time during the long journeys that separated them from their destination. These watches were far from perfect, and they were several minutes late every day, so people carrying them were accustomed to synchronizing them frequently. Therefore, when they arrived at their destination, they had only to set the new local time, without even thinking about the difference between origin and destination.

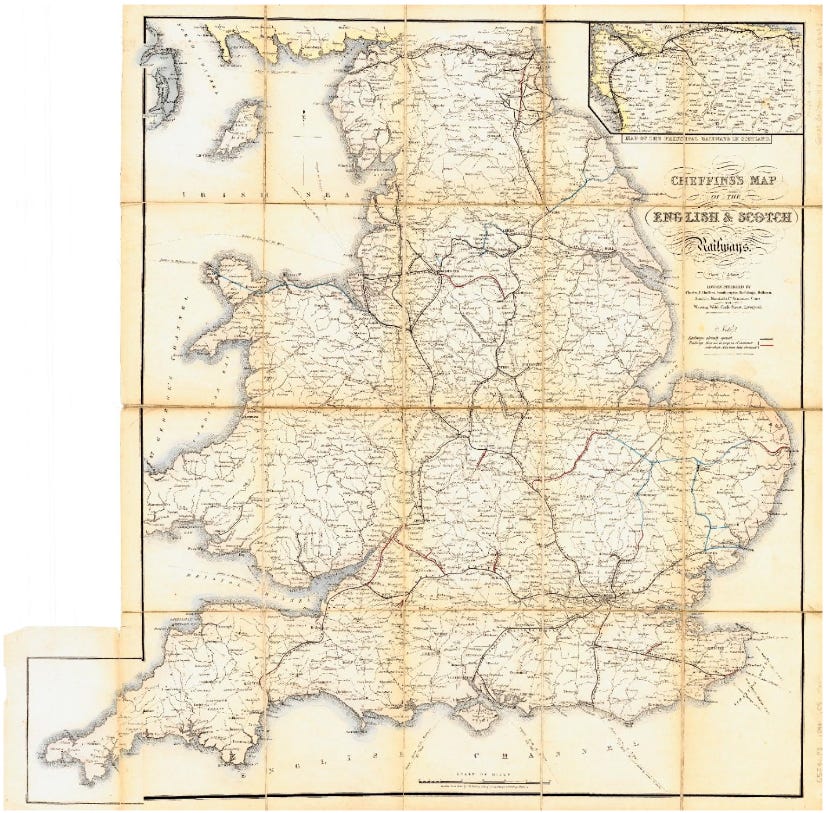

Then, technology changed this reality. On September 27, 1825, the first railway line was inaugurated, connecting the mines near Shildon with Stockton and Darlington, in northeast England. The first objective of the railroad was to reduce the cost of transporting heavy goods, mainly coal, but passenger services soon proliferated. Journeys that used to take days now took only hours in a matter of decades.

Across the ocean, on May 24, 1844, Samuel Morse publicly demonstrated how he was able to communicate in real time between Washington and Baltimore, thanks to his invention: the telegraph. These two cities, despite their two-minute difference, were in sync with each other for the first time. Long-distance communication, which until then had been limited to letters carried by messengers, became immediate.

Although the telegraph brought real-time communication between two points with different local times, it was the railroad that enforced the need for change. With the increasing demand, and a limited number of lines over which hundreds of trains ran each day, the urgency for a standardized time that would allow efficient use of the infrastructure soon became noticeable.

In 1840, the Great Western Railway became the first company to establish a centralized time throughout its network, taking as its reference the local time in London, which was set by the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. The Railway Clearing House joined this practice in 1847, and a year later all railway companies in Britain were using Greenwich Mean Time (GMT).

Over the following decades, more and more organizations began to use Greenwich Mean Time, but funny enough, local time remained the legally accepted time2. This changed in 1880, with the passage of the Definition of Time Act. This new law established that Greenwich Mean Time would immediately be the legal time throughout Great Britain, and Dublin time the legal time throughout Ireland, exactly 25 minutes and 21 seconds behind Greenwich Mean Time.

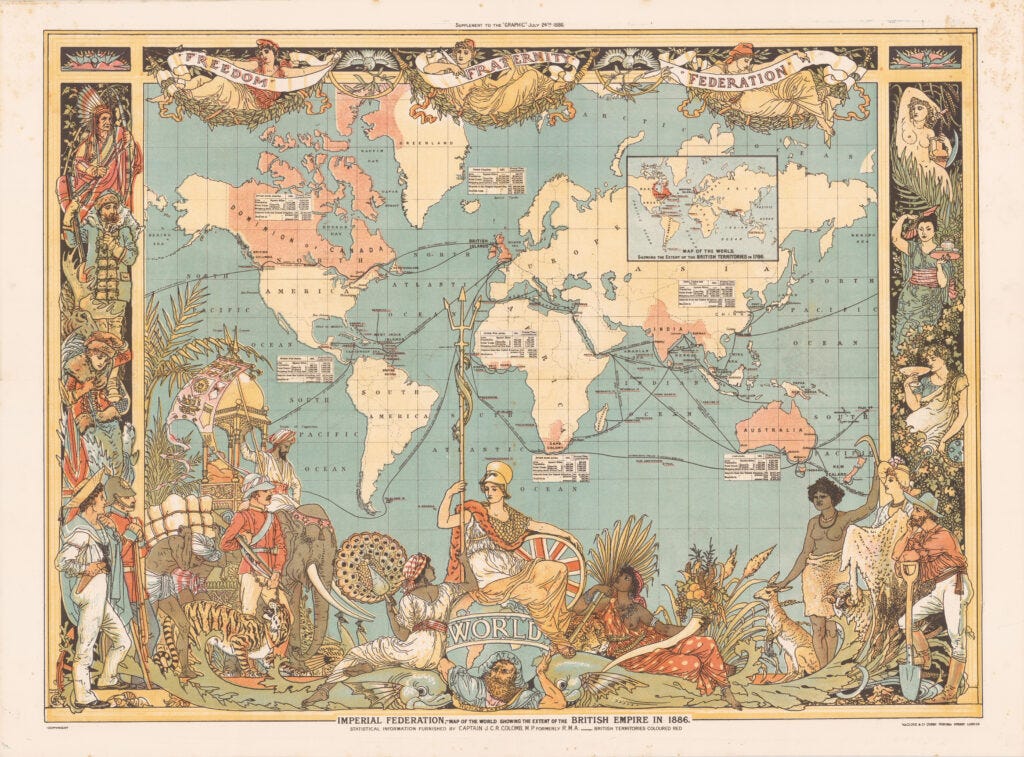

The British Empire also standardized the time used by trains in all its colonies. The first place was New Zealand, where each island took a different reference time in 1868. In India, because of its large size, two reference times were established, Calcutta and Mumbai. Interestingly, to avoid discrepancies, the railroad companies decided to take an intermediate time, that of Madras3, which would become the precursor of India's official time after independence.

In the rest of the world, the railroad and telegraph companies also took a national time, usually that of the capital, as a reference, becoming the de facto time of the territory. In 1852, the Netherlands established Amsterdam time as the official time, and it had to appear on all telegraphs sent. In France, things were much slower, as Paris time was not established as official until 1891.

International standardization

With the national problem solved, the international problem came along. In an increasingly interconnected world, the lack of standardization became obvious. Most of the countries did not have local times any more, but it was extremely difficult to memorize the differences between each country. Paris was 9 minutes and 21 seconds ahead of London, Brussels 8 minutes and 9 seconds ahead of Paris, and Amsterdam 2 minutes and 2 seconds ahead of Brussels4. A real challenge for telegraphers and train travellers.

The first to propose a solution was the Italian mathematician Quirico Filopanti, who introduced the idea of establishing 24 time zones in his book Miranda! in 1858. Each zone would be delimited by two meridians fifteen degrees apart, with a difference of one hour between one zone and the next. Filopanti, as a good Italian, established as the central zone the one located around the Rome meridian, which he considered as the prime meridian5. In addition, he also suggested the need for a universal time to be used in telegraphic communications and astronomical matters.

Although Filopanti's work was that of a true visionary, it did not set a trend per se, since his work was totally ignored and only rescued many years later. In 1876, the Canadian-Scottish Standford Fleming recommended a similar system. This also consisted of 24 time zones separated by one hour, although he assigned a letter to each one and marked as the central zone the one established around the Greenwich meridian. This time would correspond to universal time, which Fleming called cosmic time.

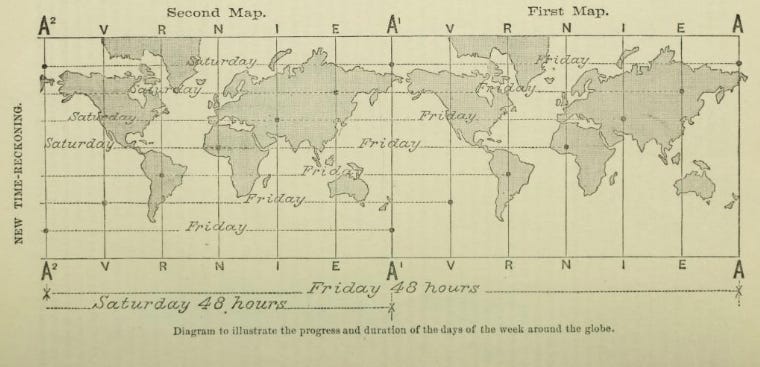

Unlike Filopanti, who only abandoned the idea in a book, Fleming wrote for multiple journals, and even published two papers that he presented to the scientific community in Toronto in 18796. One of the two articles was entirely devoted to the reasons why Greenwich should be chosen as the reference meridian, where he also defined the importance of the 180th meridian or antimeridian as the line of change of day7.

With Fleming, as a precursor, and the need of many countries to solve the problem, the International Meridian Conference took place in October 1884. The consensus was necessary, so the meetings focused on determining what the reference meridian should be. France was the biggest opponent to the Greenwich proposal, not because it wanted to impose the Paris meridian, but because it interpreted that this meridian should be as neutral as the meter was for measuring. The French delegation proposed that the antimeridian be the reference meridian, although it was rejected because it was of little use. The need to guarantee the continuity of the day on nautical charts prevailed, which could be achieved much better with the Greenwich meridian, as Fleming had already expressed in one of his articles.

Ten years later, the United States, Canada and several European states had already adopted the new time zones. The rest of the countries followed in the same footsteps, although each at its own pace. Spain, until 1900, maintained multiple official times, even in the railway network, where only the local time of the most important city prevailed. This was standardized on January 1, 1901, when Madrid had to advance its clocks 14 minutes and 44 seconds to adapt to Greenwich Mean Time.

The final result and some exceptions

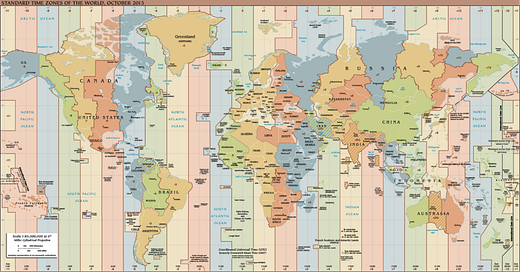

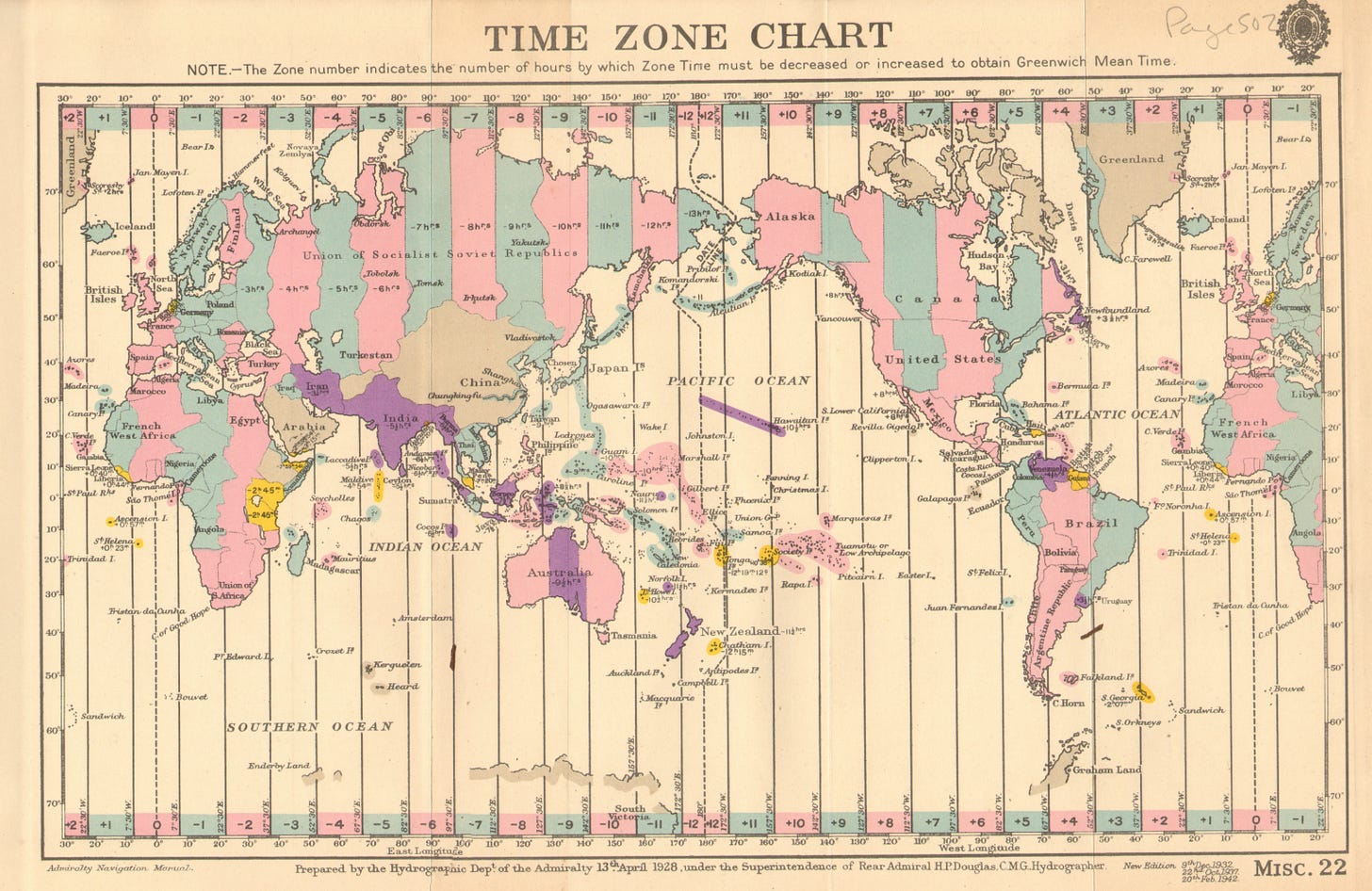

By 1928, most of the world had adopted the new time zones agreed at the 1884 Meridian Conference. This map of the time shows what the situation was.

In pink and blue are shown the countries that had adopted the time zones that corresponded to them. In purple are the regions that chose to differ only by 30 minutes from their neighbouring zone, such as Iran, India, Venezuela, or Indonesia. In yellow are the regions that still used their local time, and in gray are the countries that did not keep an official time.

This map, as expected, already shows adaptations to the strict time zones. Most countries decided to keep the time zone that best suited their territory, even if some parts exceeded one of the delimiting meridians. The larger countries, such as the United States, Russia and Canada, established multiple time zones to ensure that the entire country had a time of day that made sense and did not deviate too much from their local time.

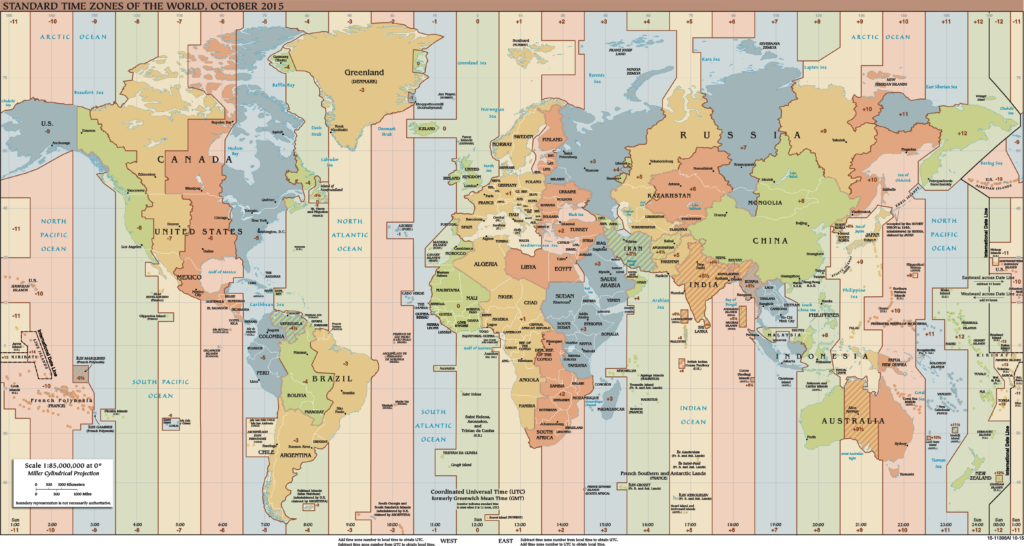

In 1940, World War II brought a change to Europe that is still with us today. Nazi Germany, when invading the Netherlands, Belgium and France, imposed its time zone according to the one used in Berlin. Spain, on the premise of keeping the same time as other European countries, also changed its time zone shortly thereafter to match the rest of Europe. World War II ended, Germany was defeated, but France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Spain kept the new time zone.

Changes like this continued to occur all over the world. In 1956, Russia opted to consolidate the time zones of its northernmost regions, so that from one zone to another they skipped two hours and not just one. China initially adopted five time zones to cover its vast territory, but at the end of the Chinese civil war in 1949, all Communist Party-controlled territory was set to Beijing time, except for Xinjiang and Tibet. Tibet eventually adopted Beijing time, but Xinjiang maintains an interesting duality between official Beijing time and the local time used by the Uyghurs.

There are some cases of countries that have opted for intermediate times. This is the case of India, which kept the time zone adjusted to Madras, 4.5 hours off Greenwich Mean Time. Nepal, after its independence, also kept that time, until a decree in 1986 decided to advance the clocks by 15 minutes. It has sometimes been claimed that this was done so that the country would live 15 minutes ahead of its neighbour, although the official justification was that this time was better suited to Kathmandu's local time.

Venezuela has also flirted with an intermediate time zone at various times in history. The first time was between 1912 and 1964, on the premise that the country was perfectly divided between two time zones, and it made sense to adopt an intermediate one. The change to a standard time zone was made after a study by the company Electricidad de Caracas, which claimed that a substantial amount of energy would be saved. In 2007, Hugo Chavez signed a law to return to the previous time zone, which was in effect until Nicolás Maduro was forced to change it back due to increased energy costs.

And speaking of energy costs, I have only one issue left: daylight saving time. I will talk about it next week, and so I will finish the trilogy I started last week, talking about the 24 hours of the day.

The pocket watch appears in France in the 16th century and, until the end of the 18th century, they were built by hand, hence their high price. When production began to become cheaper, they first became popular among sailors, given the importance of a watch for navigation. It was not until the second half of the 19th century that they began to become cheaper and more popular among the middle classes.

Actually, there was no legislation that marked the local time as legal, but there was a trial in 1858 that established the precedent. If you are bored, you can read it here: Curtis v. March (PDF).

Today’s Chennai.

Here is a website with information about the time that was set in each country before international standardization.

There have been many prime meridians in the history of cartography. The Rome meridian was used in Italy, although it was not particularly popular. In fact, when Filopanti published Miranda! Italy was not yet unified, and Rome local time was hardly used just in the Papal States.

The 180th meridian, at the antipodes of the Greenwich meridian, divides two time zones within 24 hours of each other. Or, in other words, a whole day.