The United States of Europe: a peculiar history of European federalism

A journey through some of the most peculiar ideas for federating Europe in the 20th century, by Maas, Kohr and Heineken.

In recent decades, the unity of Europe has rarely been as important as it is today. The history of the European Union is a succession of unplanned events1 that I find fascinating, but it has been told too many times already. That is why I have decided to recover some of the most bizarre ideas that have arisen throughout history to set up a federal Europe, in the purest style of the United States of America. Of course, from an absolutely theoretical perspective and, consequently, not at all plausible.

European federalism, a way of seeking peace

It is difficult to establish a beginning for the idea of the European Union, possibly because we cannot say that there was a moment when the idea of Europe emerged by itself. If we go back to the 8th century, we find the Carolingian dynasty, which, starting with Charles Martel and ending with the death of his grandson, Charlemagne, achieved a certain unity in a large part of France and Central Europe2. After the Treaty of Verdun, in 843, and the division of the territory into three kingdoms, that first attempt was completely lost.

During the next thousand years, the idea of the Holy Roman Empire was kept as a way to bring together the many political entities that divided Europe. The reality was that it was far from being uniform, as there were constant internal confrontations, whether over religion, resources or simply power. War, on a large or small scale, was a constant problem in Europe. Still, the existence of external enemies did foster a certain unity, as happened in the multiple crusades against Islam.

From the 18th century onwards, the pacifist ideal began to spread among part of European society, leading some thinkers to propose ideas that would put an end to the never-ending war. One of the first to put forward a concrete solution was Charles-Irénée Castel, with the publication in 1713 of his Project for Settling an Everlasting Peace in Europe3. In it, he suggested a European league of 18 sovereign states that would share a common economic system and have no borders. The list included some existing states, but also others that would have to be established: France, Spain, England, Holland, Portugal, Switzerland (and associates), Florence (and associates), Genoa (and associates), the Papal State, Venice, Savoy, Lorraine, Denmark, Courland and Gdansk, the Holy Roman Empire, Poland, Sweden, and the Principality of Moscow4.

After the American War of Independence, many more adopted the idea. The establishment of a federation made up of all the former British colonies seemed like a guarantee of peace that should be replicated in Europe. Immanuel Kant, in Perpetual Peace5, explores the notion that a federation of states, with ambassadors permanently based in a city like Venice, could be the solution to ensuring that there are no more unnecessary confrontations. Victor Hugo directly used the expression ‘United States of Europe’ at the International Peace Congress in Paris in 1849. Other thinkers proposed that an international organisation to which all states would have to answer to would be enough, as it was the case of the Polish biologist Wojciech Jastrzębowski in his Treatise on the Eternal Peace of Nations, from 1877.

The United States of Maas (1920)

The 20th century started strongly in Europe. All thoughts of how terrible war could be came to nothing when World War I broke out. No other conflict up to that point had taken more lives across the continent, which was a decisive factor in the proliferation of the pacifist ideal with much greater force in the years following the war. It was the moment in which more internationalist movements were created, and when some of the many that had been buried decades before resurfaced: the Communist International (1919), the International Agrarian Bureau (1921), the Labour and Socialist International (1923), the International Paneuropean Union (1923), the Radical and Democratic Entente (1924), the International Secretariat of Democratic Parties inspired by Christianity (1925).

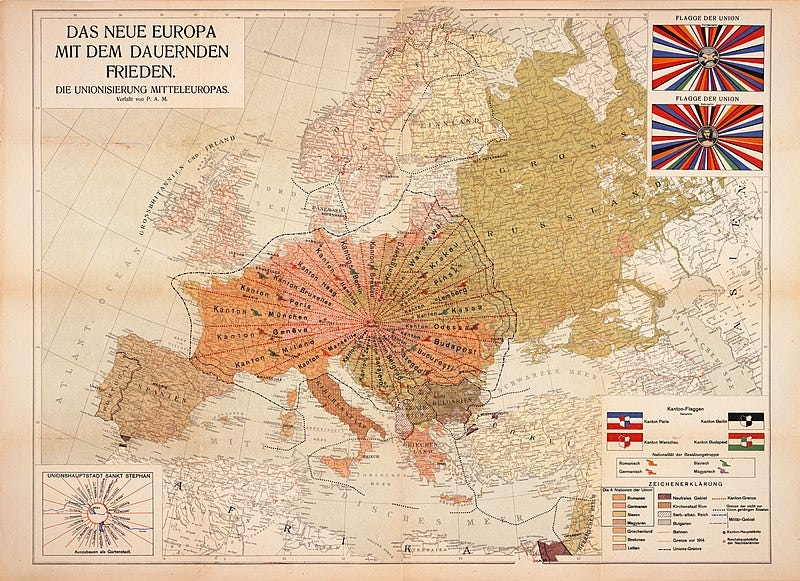

But if anything had more impact on post-war Europe than the internationalist movements, it was the widespread idea that the Treaty of Versailles had been a mistake. It clearly limited Germany's future impact, but it was far from being an agreement that could guarantee peace on the continent in the future. This led to the emergence of multiple proposals seeking another way to ensure that this would not happen again. It is within this context that The New Europe with Lasting Peace: The Union of Central Europe was published in Vienna in 1920. This map, signed by P. A. Maas6, was accompanied by a guide explaining the proposal in depth.

At first glance, the proposal is clearly idealistic and without any foundation. Maas groups together the whole of Central Europe and divides it into 24 cantons, which converge in Vienna, which would act as the capital. Each of the cantons has its seat in the most important city in the section. In this way, the author also sought to put an end to all the states and, at the same time, to break with the nationalism that had done so much damage to Europe during the First World War. Little did Maas know that the worst was yet to come. To show this proposal, the map is painted in four colours, one for each of the four nations that would be recognised in the Central European Union: Romans, Slavs, Germans, and Magyars. It also recognises the existence of other relevant nations, such as Bretons and Latvians, but denies them the recognition enjoyed by the other four.

Maas's plan also included some details about the administrative organisation and the functioning of the Union. The president would serve for a period of three years, and his position would rotate among the four nations. Everyone over the age of 20 would have the right to vote, except married women (the suffragettes still had a long way to go). The language of the union was to be Esperanto, and the education system would have to change so that half of the hours were entirely dedicated to learning the language of the Union. The plan even contemplated the future of the colonies of all the European countries, which would be grouped together for better functioning, as shown on this other map that was also included in the guide.

Like many other plans of the time, Maas' idea failed. Today, only 13 copies of the guide are known to exist, distributed among different universities and private collections.

Kohr's United States (1957)

World War II broke out, was suffered and ended. It was no longer a time for plans, but for solutions. The European Union began to take shape in 1950, with the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), and with it the direction of cooperation in Europe was set. This did not prevent other thinkers, politicians and philosophers from continuing their theoretical work on how it would be possible to reorganise Europe.

Leopold Kohr was an Austrian economist and jurist who dedicated a large part of his career to exploring the synergies between anarchism and environmentalism. This led him to publish The Collapse of Nations7 in 1957, a manifesto in which he explores how the size of states influences society. In it, Kohr argues that history shows that those who live in smaller states are more peaceful, more prosperous and happier. He also argues that federations are legitimate ways of establishing balances, provided that the member states are small and of comparable size. He cites the United States of America and Switzerland as examples of successful federations, and Europe and a hypothetical Switzerland that would have been divided into regions according to the predominant language as examples of failures.

Furthermore, he then proposes two solutions for Europe. The first is a Europe similar to the United States of America.

This first federal version of Europe would be made up of states that would be drawn with geometric lines, in the purest colonial style. Kohr assumes that this division is madness, but he points out that even if it were impossible, what it would guarantee is that the accumulation of power would not be possible as it had been during the two world wars.

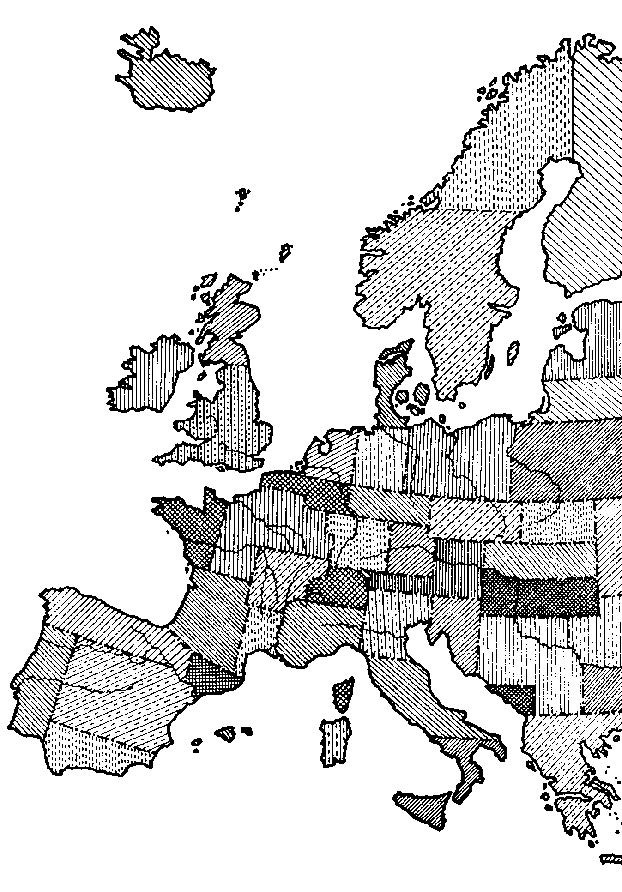

To compensate, Kohr presents a second proposal, the Europe of Small States.

In this second proposal, he admits that there are traditional borders that are best respected. To accomplish this, he takes regions that share a culture and a history, although he seeks to balance the forces by dividing the great powers of the continent. According to Kohr, this would be the only way for Europe to achieve prosperity, since it is not a question of joining forces, but of ensuring that it is divided into sufficiently small entities.

The United States of Heineken (1992)

The last proposal comes from Freddy Heineken, one of the grandsons of the founder of the great brewing empire. During his years as CEO of Heineken, he became one of the richest men in the Netherlands, but he barely had time to devote to his passion for politics. Therefore, after retiring in 1989, he embarked on a project to redesign Europe, which was published in 1992 under the title: The United States of Europe, a Eurotopia?

With this pamphlet, Heineken sought to give viability to the idea of a united Europe which, through the European Economic Community, had already begun to take shape8. The big problem he exposed was the competition between the different great European powers, since the struggle for influence would be a serious impediment to the creation of a supposed new macro-nation. To avoid this situation, Heineken contacted Henk Wesseling, a historian at the University of Leiden, with whom he worked to redraw Europe.

He proposed rearranging the borders, including the former countries of the former Warsaw Pact (except for the USSR), into regions with a similar population, between five and ten million inhabitants. These new states should try to group together areas whose inhabitants had the most homogeneous ethnic and cultural unity possible. In this way, all the great powers would be balkanised, putting aside any supposed competition. The result, published in 1992, is summarised in the following map:

In total, Wesseling and Heineken suggested 75 states. Some of them corresponded to existing nations, such as Portugal, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, Greece, and Iceland. Others involved the division of large nations, such as all the states that would be formed from France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Poland, Yugoslavia, and the United Kingdom. The list is curious, and you can consult it in detail (capitals and inhabitants) in this article.

Unplanned when it all started, but somehow planned along the way.

Of course, we cannot say that it was a peaceful unification.

I would have loved to share a map with this division, but I was unable to find any :/.

This map is often attributed to the Port Autonome de Marseille (which shares its initials with P. A. Maas), but the guide itself clarifies that the map was published by P. A. Maas, son of the popular Viennese publisher Otto Maas.

All this before the signing of the Maastricht Treaty.

Fascinating article. Any of those ideas are better than the Eurasia political union conceived by Orwell (who, let's hope not, could appear again as an accurate foreseer of the coming future)

As soon as I saw the title of this post I was hoping for Maas' map and you didn't disappoint! Have loved it ever since I saw a copy in person in the Esperanto Museum in Vienna. Never heard of the other two projects though, absolutely fascinating!