Portugal is not a small country

A journey through the propaganda of Portugal's Estado Novo, as well as some of the most iconic maps of its propaganda production.

On 28th May 1926, a coup brought the First Portuguese Republic to a sudden end after sixteen years. The military took advantage of a state structure that was almost non-existent after many years of weak governments and growing street unrest. A military dictatorship was established that same day, which two years later became the Ditadura Nacional1.

This dictatorship lacked a strong ideology or a clear government programme. It did not even have a visible charismatic figure, which allowed António de Oliveira Salazar to quickly carve out a niche for himself. As finance minister, from 1928 onwards, he managed to improve the country's accounts with a programme marked by austerity, which was well received in the government and at the popular level.

After a series of ineffective governments2 and five prime ministers in just six years, Salazar accepted the post of prime minister in 1932 and, with him, things began to change in Portugal.

The Estado Novo

If there is one thing that distinguishes a good dictator, it is a good propaganda strategy to accompany him. After coming to power, Salazar set out to change the image of the dictatorship, both domestically and internationally. The first step was to shake off the military halo that the dictatorship had established, so a new constitution was drawn up to set the new guidelines for the government. The text was published in February 1933 and put to a referendum a month later. As is often the case in authoritarian regimes, Salazar's proposal obtained a majority support of 99.52%.

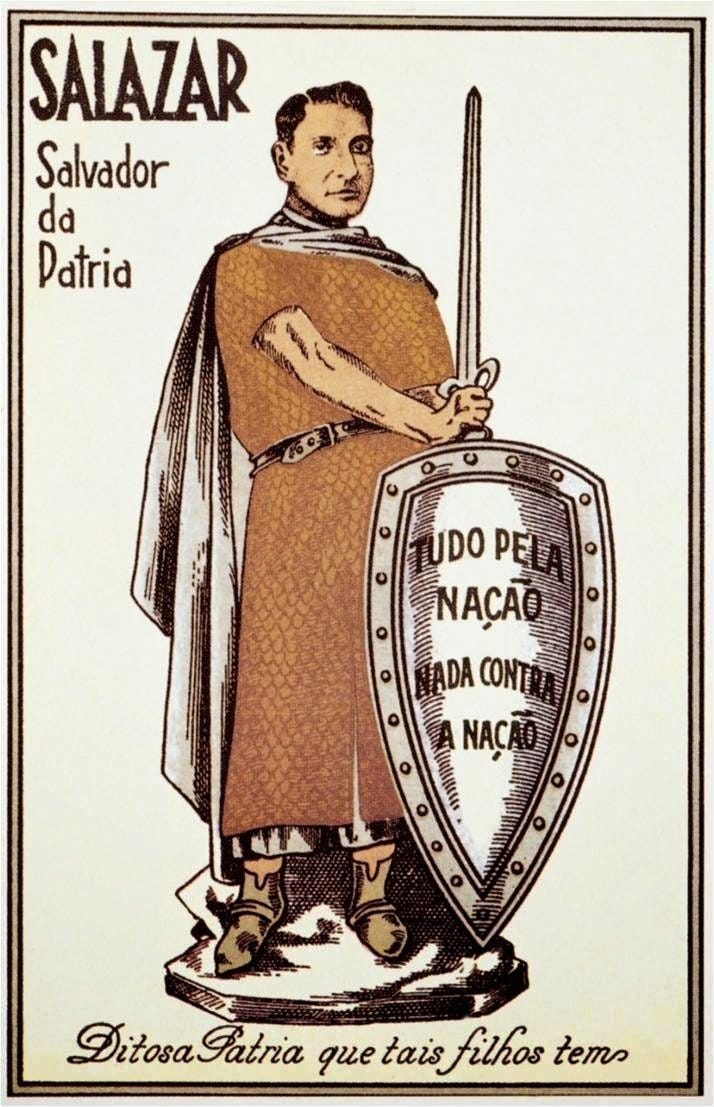

Not only was there brutal propaganda from Salazar's government, like the poster above, but also the censorship mechanisms ensured that no opposition whatsoever was visible. A total of 806,166 people voted in favour, and only 6,190 voted against. And well, 487,364 people abstained, but the government considered that abstention to be a vote in favour, so they were counted as “yes” votes. The constitution came into force on 11 April 1933 and, with it, the Estado Novo3.

The advisor who proposed many of these changes was António Ferro, a writer and journalist who had shown great interest in the great dictators of Europe. After three interviews with Benito Mussolini and one with Miguel Primo de Rivera4, Ferro had gone deeply into fascism and the authoritarian regimes of the time, which was key to mounting a propaganda ideology that could sustain the new government. Salazar recognised the importance of his support, and this led him to create the Secretariado Nacional de Informação5 in October 1933, with Ferro in command.

Ferro's propaganda machine had many similarities with those of other European dictatorships. As the poster above shows, the propaganda equated Salazar with figures such as Alfonso I, the first king of Portugal, in a search for continuity with the country's best historical rulers6. In the same vein, Ferro floated traditional values under the slogan ‘God, Country and Family’, in which cultural roots took precedence over modern life. Everything rural gained prestige, at least at the propaganda level, while any ideology that could jeopardise those values, be it democratic liberalism or socialism, was rejected.

This rejection of the idea of internationalism led Salazar to forge the idea of Portugal as a neutral country, with no interest in the affairs of the world beyond its borders. Of course, like many other European countries, he did not hesitate to justify his colonial empire through his role as a civilising country. After all, what would Mozambique and Angola have done without Portugal?7

Portugal is not a small country

As part of Ferro's brutal propaganda campaign in the early years of the Estado Novo, from 16 June to 30 September 1934, the First Portuguese Colonial Exhibition was organised in Porto. To attract as many visitors as possible, replicas of the main monuments from the colonies were built. The gastronomic wealth from all corners of the empire was exhibited, and even a zoo was created with exotic animals from African and Asian territories. The aim was to vindicate the greatness of the colonies, but also to show the great investment opportunities that could be found for businessmen beyond the metropolis.

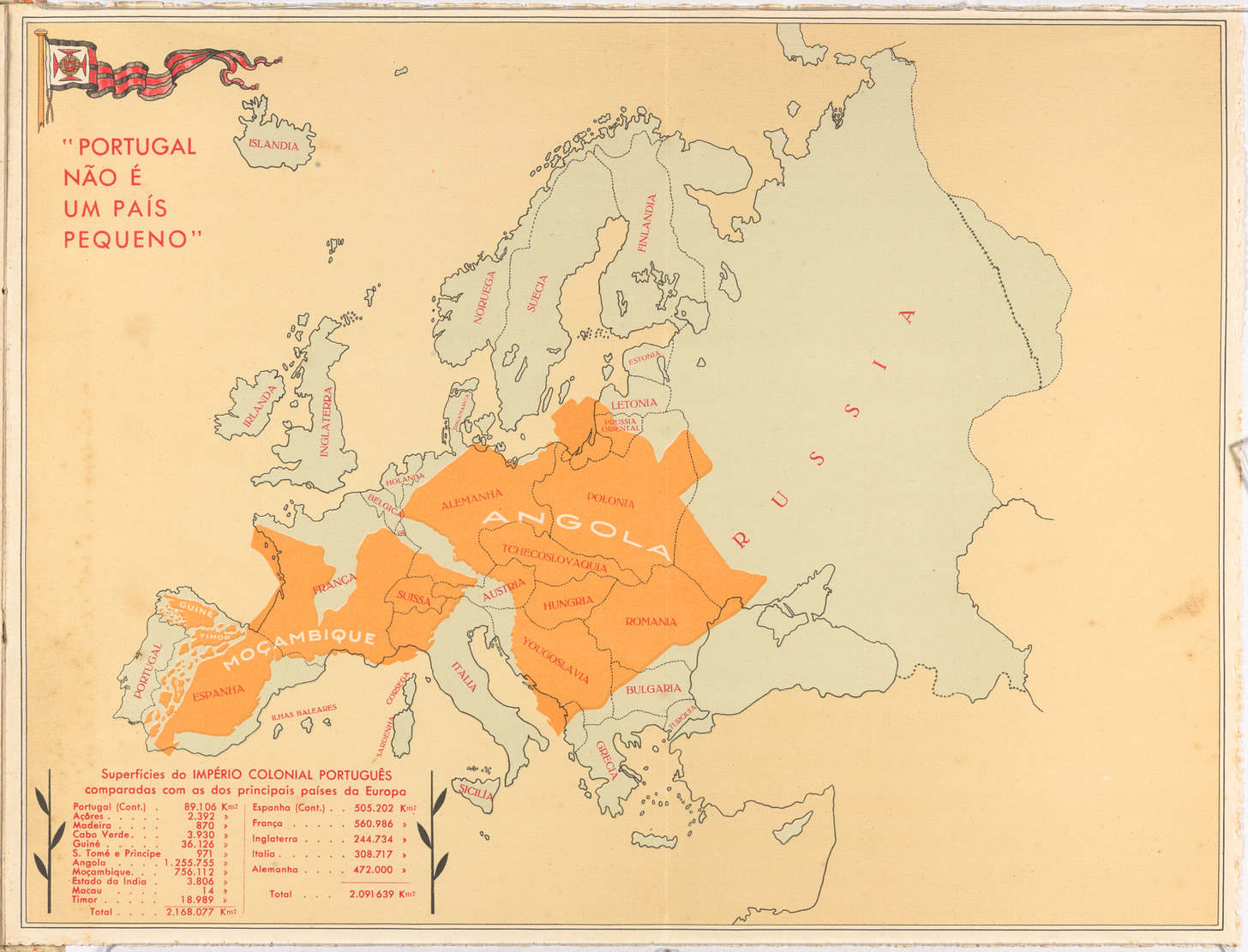

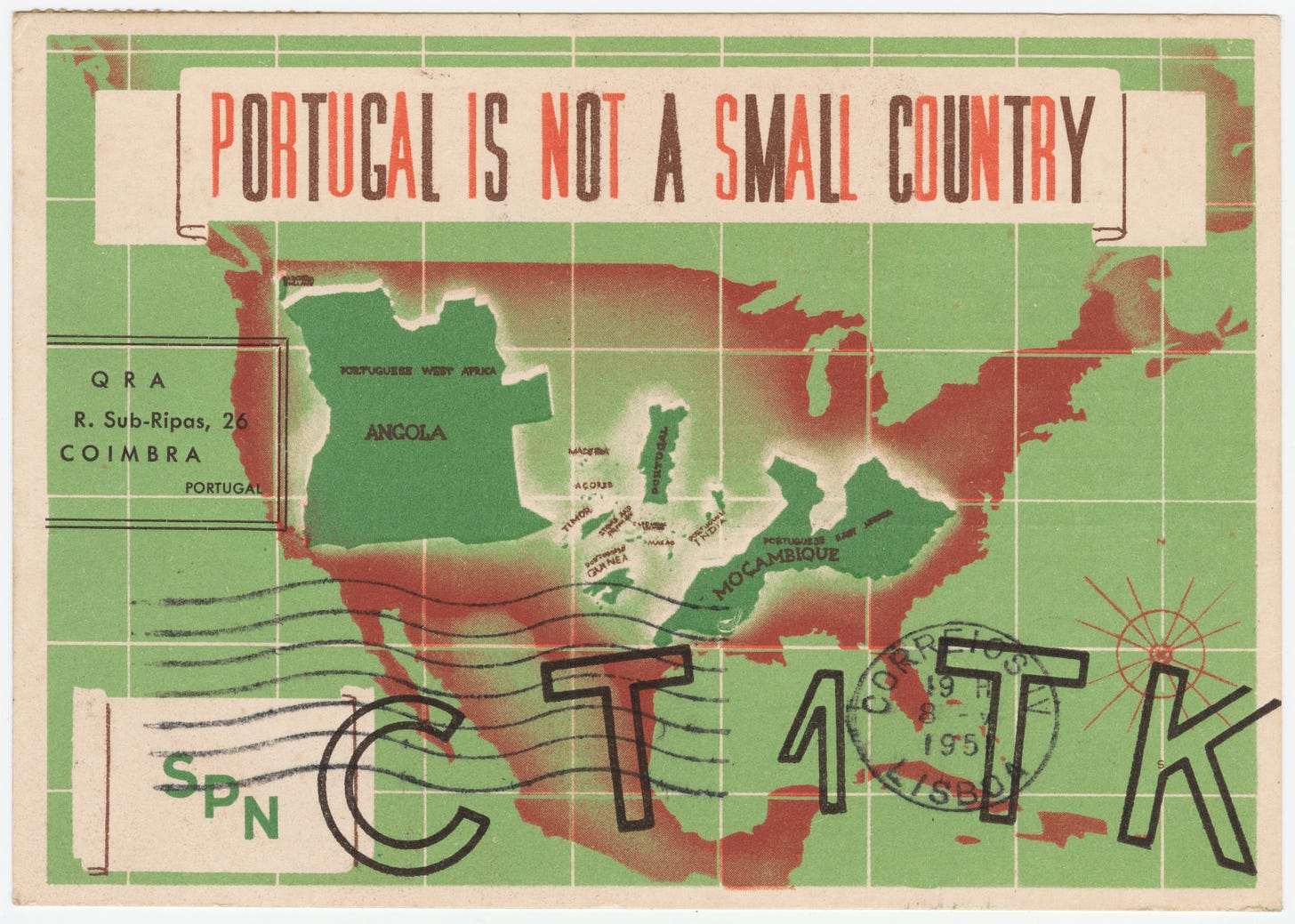

To promote the exhibition, a booklet was published, with great level of details. In the centre of that brochure was what is possibly the most iconic map of all the Portuguese propaganda of the time: Portugal is not a small country.

This map is a real gem of persuasion. On the premise that the entire colonial empire was as important and valuable as the metropolis, Henrique Galvão, the exhibition's director, made a direct comparison between the total size of the Portuguese colonies and the rest of the European continent. Angola and Mozambique appear in yellow, with their imposing size, but also Guinea-Bissau, Goa, East Timor and all the smaller colonies in Africa and Asia.

As if that were not enough, in the lower left part of the map there is also a list of all the colonies and their surface areas, which totalled more than 2.1 million square kilometres. Overall, more territory than the sum of Spain, France, England, Italy, and Germany together. To no one's surprise, in a magnificent play on numbers, these five countries did not include any of their colonies or non-continental territories.

The map was so successful that it was reprinted in multiple formats over the years, as well as in other languages such as French. The idea was good, so Salazar wanted the propaganda to be spread as far as possible. On the one hand, to enhance patriotic sentiment, but also to be considered a country of weight in the eyes of the other European countries.

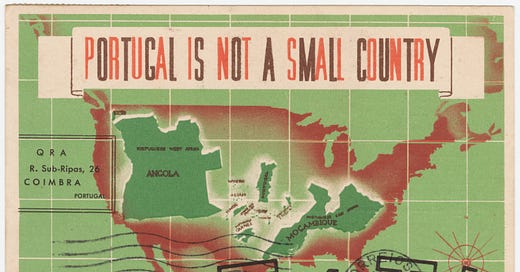

In 1951, taking the same idea further, this other map was published in postcard format addressed to the United States. In this case, Portugal and all its colonies are shown within the contiguous United States, scattered to increase the perception of territorial equivalence. As the Portuguese propagandists were clever, in this case no comparative table of extension in square kilometres was included, since if they had done so they would have barely reached 25% of the total territory of the United States.

What this map did have on the front was a statement that was not included in the European versions: ‘By its history, Portugal contributed more than any other country in the world to the discoveries and to the extension and predominance of Christian civilization’. Portuguese propaganda knew that the United States was a predominantly Christian country, not a Catholic one, so it had to build bridges to get the power that dominated the West to take it into account.

This strategy of positioning Portugal as the discoverer of the world was not new on this map, but was something that had been used previously, as can be seen on this map from 1940.

This map, the work of Roberto Araújo, under the direction of the Secretariat of National Propaganda, was created for the Portuguese World Exhibition. This new exhibition, which took place in 1940 in Lisbon, commemorated the 800th anniversary of the founding of the Portuguese state (1140) and the 300th anniversary of the restoration of independence (1640)8. On this occasion, the guiding theme was no longer the colonies, but the Portuguese discoveries and how much they had contributed to the knowledge of the world.

Perhaps the first thing that catches the eye on Araújo's map is its aesthetics. He makes the most of the cartographic knowledge of the time, but seeks to resemble the most characteristic maps of the 15th and 16th centuries, to generate the authority that we ascribe to historical documents. This is achieved with the compass roses and the marked navigation lines, typical of the maps that ships carried with them in the 16th and 17th centuries to sail the oceans.

The statement about Portugal's discoveries that appears in the title of the map is accompanied by 19 voyages made by Portuguese explorers between 1482 and 1660:

Diogo Cão (1482-85)

Bartolomeu Dias (1486-1487)

Vasco da Gama (1497-1498)

Pedro Álvares Cabral (1500)

João Álvares Fagundes (1500)

Gaspar Corte Real (1501)

António de Abreu (1501)

Francisco Serrão (1501)

Afonso de Albuquerque (1507)

Jorge Álvares (1514)

Fernando de Magallanes (1520)

Esteban Gómez (1525)

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (1542)9

António da Mota (1542)

João Martins (1588)

Pedro Fernandes de Queiroz (1606)

Emanuel Godinho de Erédia (1601)

João Vaz de Torres (1606)

David Melgueiro (1660)

Araújo's work intentionally only describes the routes followed by all these explorers, but does not dwell on what exactly these explorers discovered. Appearances are important in propaganda, so it was enough to have red lines repeatedly crossing all the oceans to give the impression of having reached every corner of the world.

Angola is not a small country

In December 1961, the Indian army occupied Goa and the rest of Portuguese India and, with this, the decolonisation of the Portuguese empire began. Salazar and his government had to dedicate more and more resources to appeasing the multiple revolts in the rest of the colonies, which meant an increasing cost. In 1968, Salazar stepped down due to health problems and was replaced by Marcelo Caetano, who maintained the policy of preserving the African colonies at all costs. In 1974, the Carnation Revolution put an end to the Estado Novo and, just one year later, Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde and Timor-Leste declared their independence.

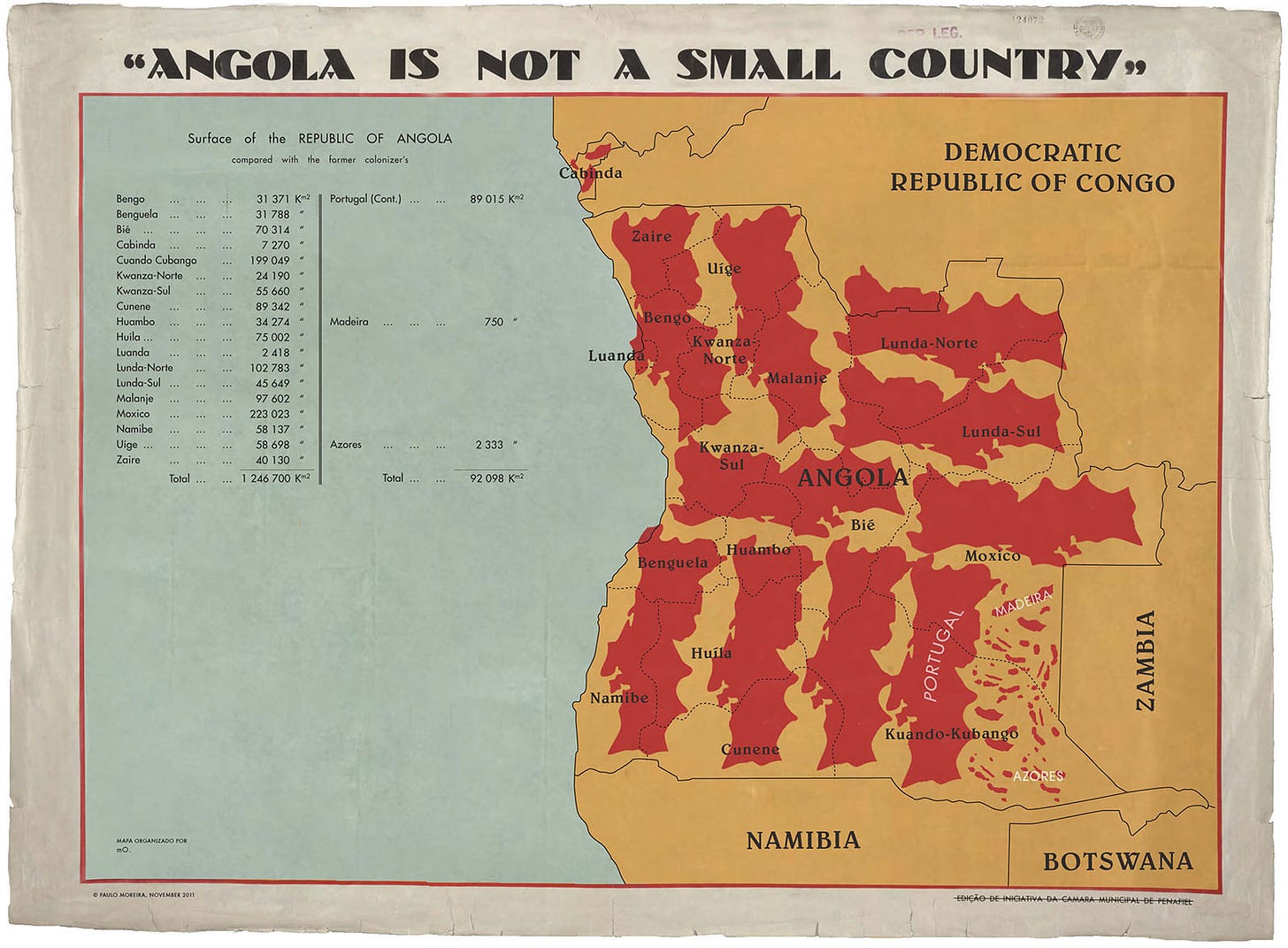

In 2011, the architect Paulo Moreira began work on an exhibition to reclaim Angola's development in recent years. Through a sponsorship campaign, he raised funds for all the promotional material and opened the exhibition in Porto on 2 December 2011 with the title ‘Angola is not a small country’. Not only did the title of the exhibition recall that map by Henrique Galvão in the 1934 exhibition, but Moreira also created a map to match it as a central part of the exhibition.

Moreira's map uses the same aesthetic as the French version of Galvão's map, so that the parallelism is inevitable. He takes the size of Portugal, together with Madeira and the Azores, and replicates it ten times on the map, to show that it can easily be contained within the total area of Angola. As in the original work, Pereira presents mathematical tables in which he adds up the territory of the 18 Angolan provinces, with a total of 1.23 million square kilometres, and compares it with the relatively small 92,000 square kilometres that Portugal has today.

Beyond the map, the project sought to show the world a broad perspective on the reality of Angola. It encompassed the vision of citizens, of the authorities, of multiple NGOs working in the country, all with the participation of several Angolan universities. In addition to Moreira, seventy Angolan students worked on the exhibition. This helped to ensure that it was not just another Portuguese campaign about one of its former colonies, but rather a Portuguese helping the citizens of Angola to tell the story from their perspective.

National Dictatorship.

Clearly, the coup did not change the dynamics that already existed in Portugal of weak and short-lived governments.

New State.

Miguel Primo de Rivera was a dictator who ruled Spain from 1923 to 1930.

National Information Secretariat.

Here we can see the great influence that Italian fascism had on Ferro and his way of structuring propaganda. Mussolini did basically the same with his figure, but with the Italian referents, the Roman emperors.

Note the sarcasm.

Which put an end to 60 years of dynastic union with the Spanish monarchy.

Today, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo is considered to be Spanish by origin.