How did North get to the top?

North has not always been at the top of maps. It has travelled through centuries and civilisations to get there.

Maps are the mechanism mankind has found to represent the surface of the Earth. As much as some people like to talk about some maps being more correct than others, the truth is that it is nothing more than a convention.

Someday I will elaborate on projections and the reasons why there are none that are correct and yet, at the same time, the vast majority of them are usually useful for some purpose. Meanwhile, today, I will focus on this mania we have for drawing maps with North at the top and where it comes from1.

At the beginning, there was no consensus

For obvious reasons, we can only discuss maps that we have records of, so we will have to skip a large part of human history and start with the first civilisations. If we look at the earliest maps, there is no consensus as such, but there is a common reason for orienting the maps. Each ancient cartographer placed at the top what was culturally most important to them.

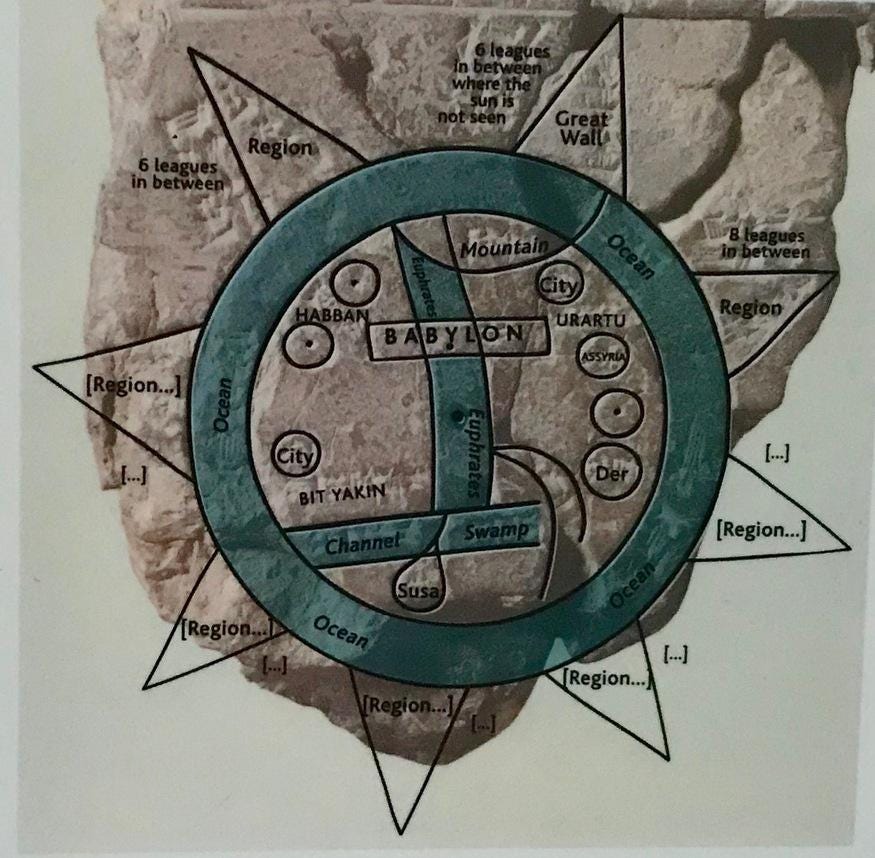

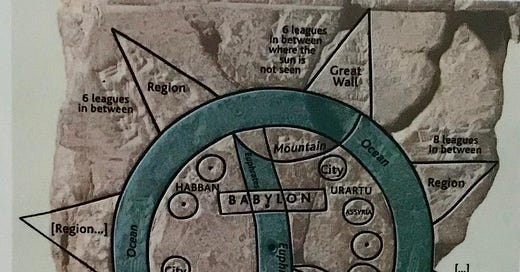

If we go back to one of the earliest maps of the world, the Babylonian map, we can see that it is oriented with Northeast at the top. It may seem uncanny, but we can trace an explanation to the importance of the winds for the Babylonians. Although it is commonly believed that there is only one definitive method for determining directions, namely North, South, East, and West, the reality is that there are as many possible directions as there is creativity. In the case of Babylon, the system of directions was based on the prevailing winds of the region. And among all the winds, the North-East wind was the one associated with the goddess Ishtar, the most significant of all their pantheon.

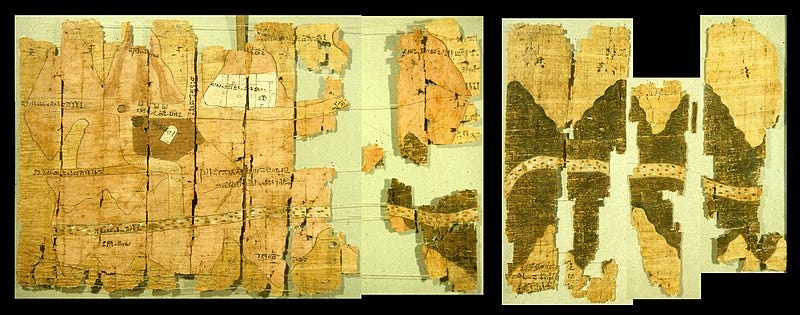

At a similar time, a few thousand kilometres away, Egypt had its particular way of understanding the world. All the papyri that have been preserved have the South at the top. The interpretation given by scholars to this fact was the importance of the Nile River in Egyptian civilisation.

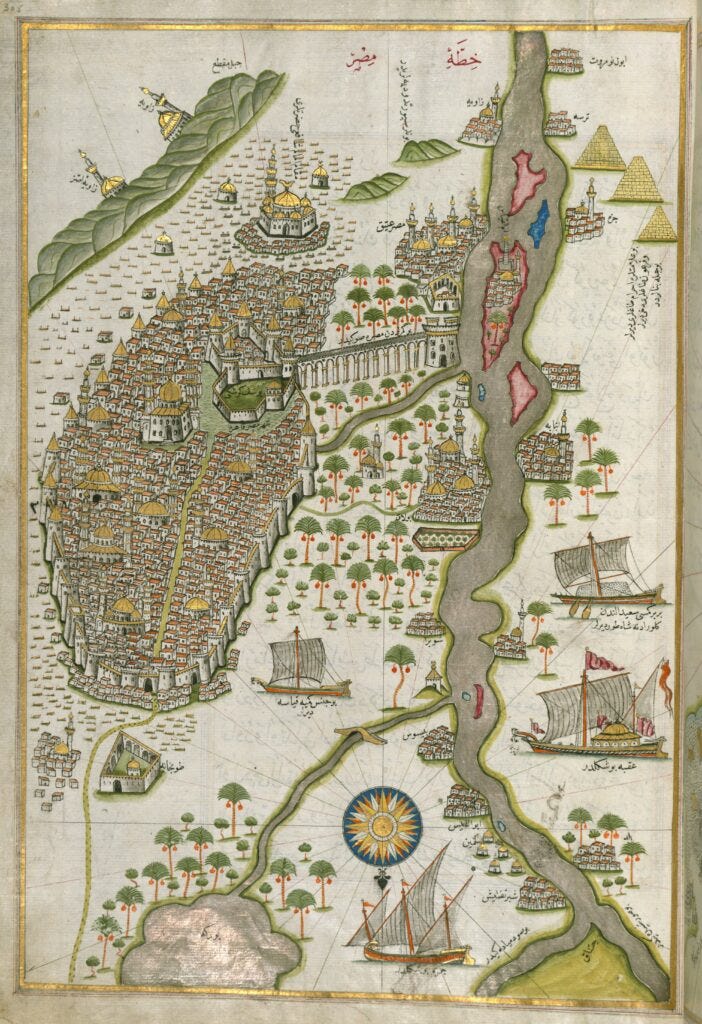

All the great cities and the wealth of the multiple empires that occupied the region for more than three millennia were linked to the Nile. There was nothing in the Egyptian conception of the world more important than the river that articulated their civilisation from South to North. That is why, on their maps, the Nile River always flowed downwards. Below you can see it in the Papyrus of the Mines2 and also in another later map, from the 16th century, which is drawn on the same tradition.

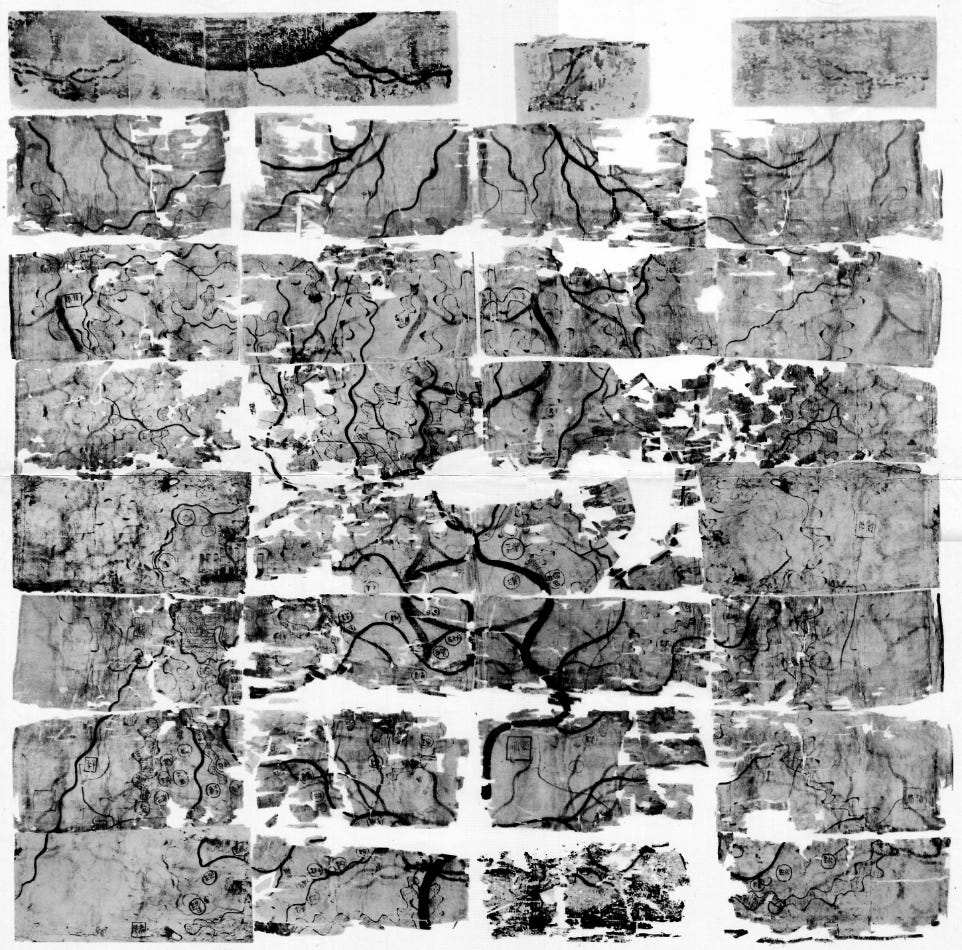

In China, on the other hand, we find multiple maps without a marked tendency to orientate them. For example, the Mawangdui topographical map, found in a tomb in 1973, was dated around 170 BC and depicts the kingdom of Changsha, ruled by the Han dynasty, and the independent state of Nanyue. The map is oriented with the South at the top, and there is no scholarly consensus as to why this determination was made.

The Middle Ages turned eastward

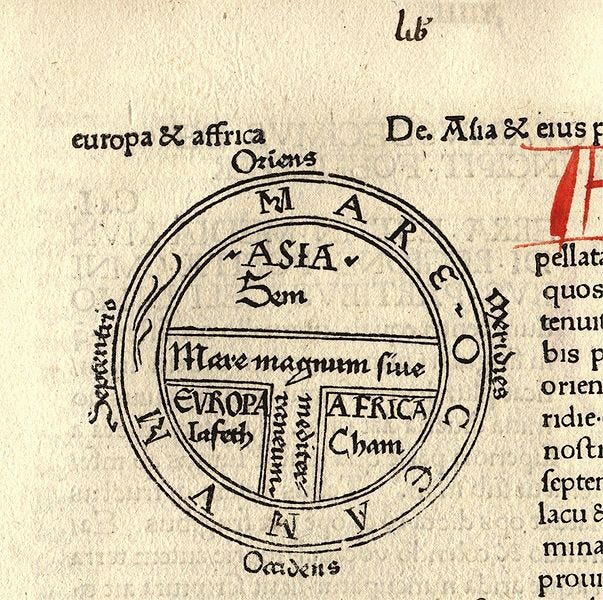

The Middle Ages was a very intriguing period in Europe. Without falling into the fallacy of labelling the period as dark and backward3, we can say that during this time, religion was the driver of most of the knowledge. Within Christianity, a type of map was developed that, beyond seeking to represent the world, intended to inculcate a particular religious vision. This is how the T and O maps appeared.

In Etymologies, a work written by Isidore of Seville in 625, we come across one of the first T and O maps, with a schematic format that is particularly useful to describe the concept. Three continents are considered: Europe, Africa and Asia, each associated with one of Noah's sons4. To divide the emerged lands, the seas are shown in schematic format: on the outside, in the shape of a circle, the oceans; on the inside, in the shape of a T, a series of waters representing, depending on the map, the Mediterranean and Black Seas, as well as the Nile and Don rivers.

It is not relevant how faithful these maps are to reality, but much more significant what they can transmit. At the top is Asia, to the East, the continent where the Garden of Eden has historically been located. In the centre, just above the T, is Jerusalem, the sacred city of all Abrahamic religions. All these ideas are much more evident in this other map of T in O, published by Beatus of Liébana in the 8th century, following the instructions of Isidore of Seville, Ptolemy, and the Bible.

In the end, North was at the top.

Before anyone misreads me, I insist: there is no consensus. It is often vehemently asserted that the North is placed at the top for one reason or another, but it is most likely that it was a compendium of circumstances that led to this.

Firstly, we have to refer to the classics. Already during the Middle Ages, Ptolemy's work had been praised by many scholars, but throughout the 15th century, the great artists raised Ptolemy's Map of the World to the pinnacle of classical cartography. And of course, this map had North at the top.

This copy is a 15th century reconstruction based on Ptolemy's descriptions in his Geographia5. This served as inspiration to the great cartographers of the 16th century like Gerardus Mercator or Abraham Ortelius. But these maps also had another important purpose: to be used for navigation and exploration during the Age of Discovery.

Again, from a Euro-centric perspective, the navigation of the seas had been guided, to a large extent, by the North Star as a reference point, which also pointed North. Just in case these were not enough, it was also the time when the compass from China became popular in Europe. It is said that in China this tool was always used to identify the South, but by simply painting the opposite side of the compass a different colour, the compass was able to point North.

These three conditions together definitively marked the North on the top of maps in Europe, at least in the case of world maps and any map covering a large territory. Colonialism, imperialism, and the imposition of European culture around the world throughout the Modern and Contemporary Ages did the rest of the work.

But, does the orientation of a map matter?

Yes, it does. And it matters a lot. The set of circumstances that led to the North being at the top of the maps may not have been planned, but there is an intention that this should remain so.

Just as a matter of how we analyse an image when we first look at it, everything on the top and left side6 is much more relevant. This, coincidentally, leaves North America and Europe in the most exposed areas of a normative world map, while leaving other continents such as Africa or Oceania in secondary areas.

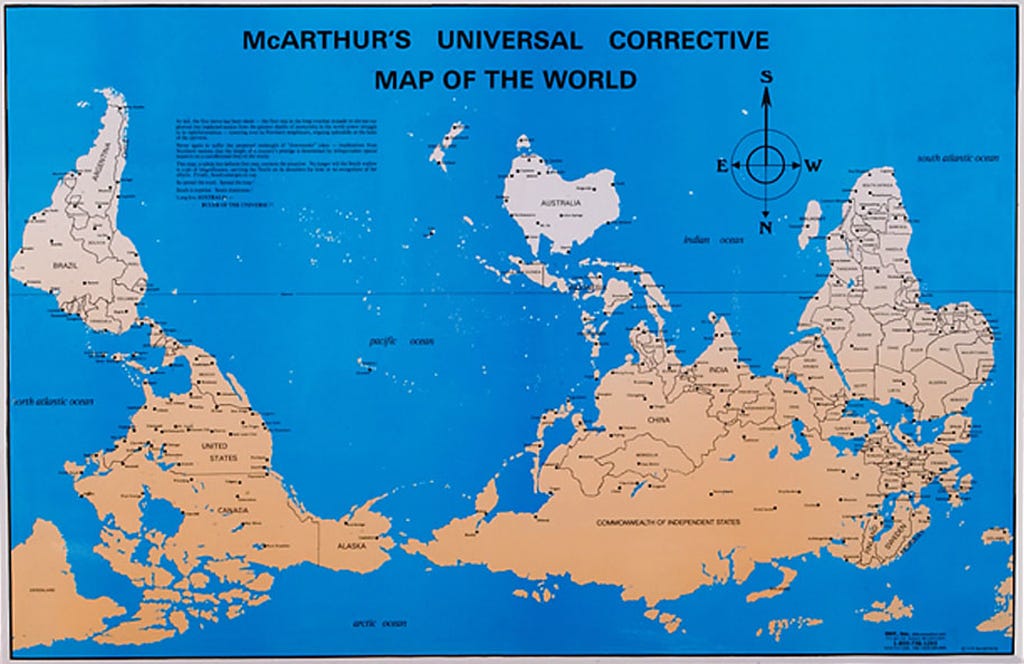

The Australian McArthur, fed up with this, in 1979 published a correction to the world map.

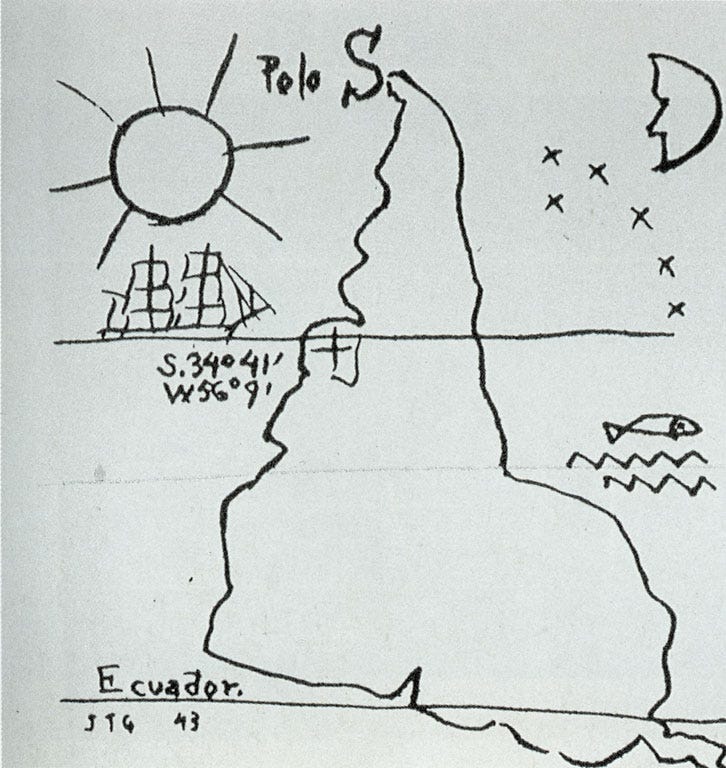

McArthur might have published the most iconic map, but it was not the first. More than three decades earlier, in 1943, the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres García published his renowned América Invertida. In this work, South America is depicted, but with the South oriented at the top, rather than the usual way of showing the continent.

This work was published together with the manifesto entitled The School of the South, which claimed that, for South Americans, the obvious point of reference had to be the South. Most of the continent is located in the Southern Hemisphere7 and, in that part of the world, the reference point is no longer the Pole Star, but the Southern Cross.

There is no denying the obvious propagandist charge of the map, but it is nonetheless a relevant perspective to have. The viewpoint provided on this map is influenced by the indigenous traditions of the southernmost region, which, as mentioned above, were displaced by the imperialist vision that occupied the continent.

If you like videos, I also recommend this one from Map Men covering the same topic in a different way.

Or rather, you will have to take my word for it, since it is challenging to interpret it simply by looking at the paper and without having the context.

Please don't be that kind of people.

It is also the case in this other map.

Interestingly and importantly, we have no copies from the period.

It can be the top-right side in the case of a native language that writes from right to left.

Although the position of the equator is exaggerated, it is true that 90% of South America is in the Southern Hemisphere.

I came here to include América Invertida but you already knew about it! Bravo

English version, Miguel? 🔥🔥