The first regional maps and the first world map

A journey through some examples of the conceptualisation of the surrounding territory, which grow in extension until we reach the first world map of which we have evidence.

Have you ever wondered at what point human beings began to represent the surrounding territory in the form of maps? If we don't want to fall into survival bias1, we cannot say with complete certainty when an individual first symbolically represented his or her environment. What we do know for sure is that, throughout the Palaeolithic period, they appeared in many societies around the world. Many authors today consider the oldest map to be inscribed on a mammoth tusk found near Pavlov in the Czech Republic in 1962.

This piece was found inside a site2 linked to mammoth hunters and is dated to 25000 BC. According to archaeologists at the site, the geometric inscriptions on the tusk correspond to the nearby river valleys as well as the surrounding mountain slopes. This symbolic representation of the territory may have had an important value for the hunter-gatherer groups who occupied the area, although it is not possible to say how useful this map really was. In fact, it is not even possible to say with certainty whether this set of lines really was a map.

With this in mind, today we are going to go through some examples of the first regional maps, up to the first world map.

The map of Abauntz Cave

Since time immemorial, human beings have recognised the importance of preserving a mental record of places and routes useful for their needs. It was essential for the group to know where to find water, fruit trees, and animals in the area they lived in. But, like any other kind of knowledge, it was difficult to preserve the insight about the surrounding landscape from one generation to the next because of communication limitations.

With the evolution of language and symbolic thinking, humans learned to capture these details of their environment in various materials. It is most likely that the first maps or sketches representing a region were drawn on wood, or even on the mud of sandy areas, just to meet a temporary communicative need in a specific situation. Given the ephemeral nature of wood as a material or clay as a support, no sample has survived to the present day (that we are aware of). Fortunately for us, however, there were some groups that used more durable materials.

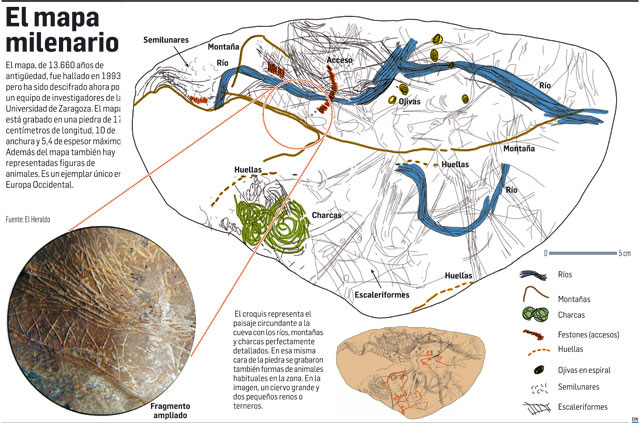

The stone above corresponds to one of the limestone stones, weighing more than a kilo and twenty centimetres long, found in Abauntz Cave, in Navarre, northern Spain. The archaeological team led by Pilar Utrilla Miranda found it in 1993 and, for more than fifteen years, they dedicated themselves to analysing all the traces and incisions on the stone. Initially, they appeared to be just representations of animals with some lines linking them, but they gradually realized that there were certain similarities with rivers, mountains, and roads.

The research results were published on July 21, 2009 in the Journal of Human Evolution3. Utrilla's team had not found yet another sample of rock art, but one of the earliest known maps in human history. One of the two stones found contained a detailed plan of the surroundings of the Abauntz Cave, and was dated to 11660 BC.

In the map of Abauntz Cave, as in other Palaeolithic maps, the cartographer’s interest in representing something useful for his social sphere prevailed over the need to be faithful to reality. Distances and directions were not as relevant as the visual markings of the area. These marks would allow individuals to move comfortably around the environment.

The Saint-Bélec slab, the map of a principality

The Abauntz map, despite being represented on a stone, seems to have a use limited to the small group that inhabited the cave and needed to maintain certain information about the environment. It is not a need to represent the territory itself, but a way of showing the group how to get to nearby places useful for survival, such as the river or water holes. As societies became more complex, maps also began to serve other purposes.

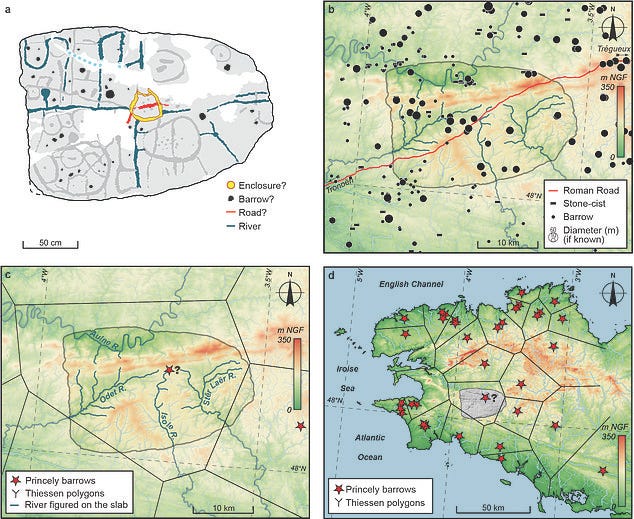

The slab in the photograph above was originally found in 1900 at Saint-Bélec, a prehistoric burial site in Brittany, by Paul du Châtellier. It was part of a cist4 almost four metres long, two metres wide and two metres high. This particular slab was 2.2 metres long and 1.5 metres wide, and it showed signs of having been part of a larger slab, but the upper part was missing. Du Châtellier took this piece home, and it remained there in the basement until it was rediscovered in 2014.

Several researchers who had read du Châtellier's original reports already suspected that the slab might represent a map. For four years, a multidisciplinary group studied the piece in detail. As a result, in June 2021, they published an article in the Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française5 of the Société préhistorique française. The article explained that, in fact, the carved slab of Saint-Bélec showed a map of a vast territory.

Fortunately, the piece had not been exposed to the outside for a long time, which meant that all the grooves could be studied using photogrammetry. The researchers soon realized that the lines shown on the rock corresponded very closely to the rivers in the Brittany region where it had originally been found. The circles and squares could be interpreted as settlements and burial mounds. In addition, the surface of the slab was lightly carved with small reliefs that had similarities to the topography of the terrain. In total, the slab represented an area 30 kilometres long and 21 kilometres wide, with a similarity of 80% compared to present-day maps.

The piece was dated to the Bronze Age, around 4 000 years ago. The researchers' information and the fact that it was found in a grave suggests that it might be a map of a Bronze Age principality. This provides the map with a sense of control over a territory that was previously uncommon in Europe. In fact, several scholars consider the Saint-Bélec slab to be the first map of Europe.

Babylonian Map of the World

If maps of vast regions were rare in antiquity, maps designed to represent the entire world were even more extraordinary. This makes sense, since it was not enough for a society to have a sense of itself and relate to a particular territory. It was also required to have a sense of other groups beyond occupying different spaces. This, which may seem obvious through the lens of the present, may not have been relevant until relatively recently.

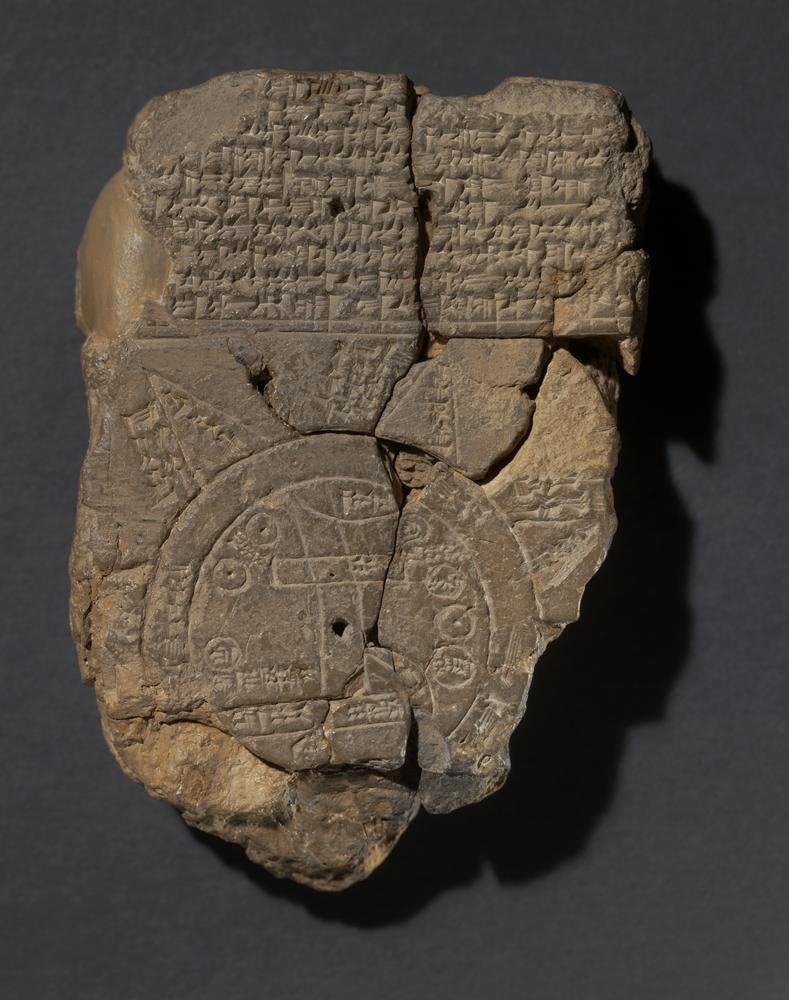

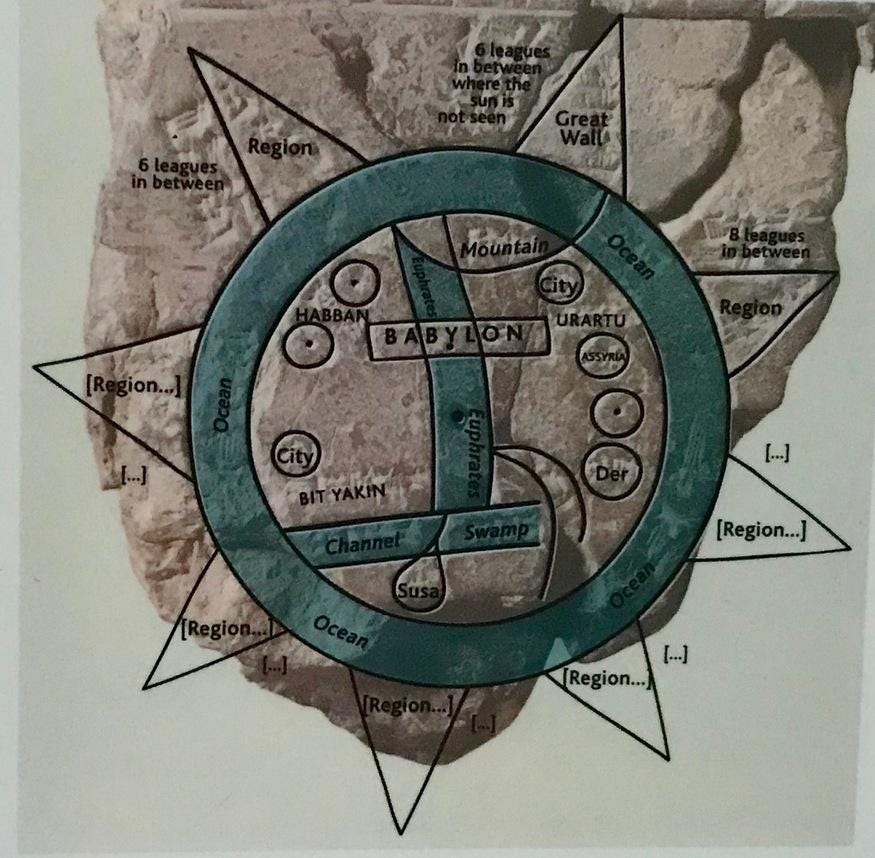

The oldest-known map that attempts to represent the entire world is the Babylonian map of the world, which now resides in the British Museum in London. It was created in Babylon around 500 BC as a copy of an original 200 years older, which has not survived to the present day. It is a clay tablet with drawings and inscriptions showing the Babylonian view of the world.

The map shows two concentric circles, as well as seven triangular areas surrounding the outer circumference. The area inside the circle represents the central continent, where the city of Babylon occupies the central place, represented by a rectangle. With other geometric figures, the Babylonians also placed and named other contemporary peoples such as Assyria (northwest of Babylon), Urartu (present-day Armenia, north of Assyria) and Habban (present-day Yemen, southwest of Babylon). Although the Babylonians were aware of the Persians and Egyptians, they were entirely ignored in this depiction, possibly because of clashes with them.

Topographically, the map depicts mountains to the north, where the Euphrates River rises, flows through the city of Babylon and empties at the bottom of the map into the two circles. These two concentric circles correspond to the salt waters, i.e. the sea. The outer text on both sides of the tablet describes that the purpose of the map is to show the whole world. The emphasis on the distance between places that accompanies the map suggests that it was intended to locate distant regions, even beyond the known world.

The text on the reverse of the tablet describes the seven triangular regions, which it calls islands, in detail, although it is clear that the Babylonians knew little about these places. The first island corresponds to the one depicted in the southeast, and the subsequent islands are described in clockwise order. Only the brief description of three of the seven islands is preserved, of which it says briefly: ‘Place of the rising sun’, ‘The sun is hidden and nothing can be seen’, and ‘Beyond the flight of birds’.

As a last interesting detail of this first map of the world, we have to talk about orientation. As I commented here weeks ago, not all maps point north. In this case, the map places northwest at the top. This is because, unlike our system of cardinal points, the Babylonian system of orientation was based on the prevailing winds, the northwest wind being a wind blown by the goddess Ishtar.

Survival bias (or survivorship bias), when applied to history, is to limit analysis to what has survived to the present day, ignoring all sources that may have existed but have not been preserved or found.

You can find more information about the site and the piece on the official website.

Great stuff, Miguel. I had no idea about prehistoric maps. I wonder if there are more of them out there waiting to be discovered. I had written about Pavlov before, but its fascinating to learn that map-making was among their many achievements.